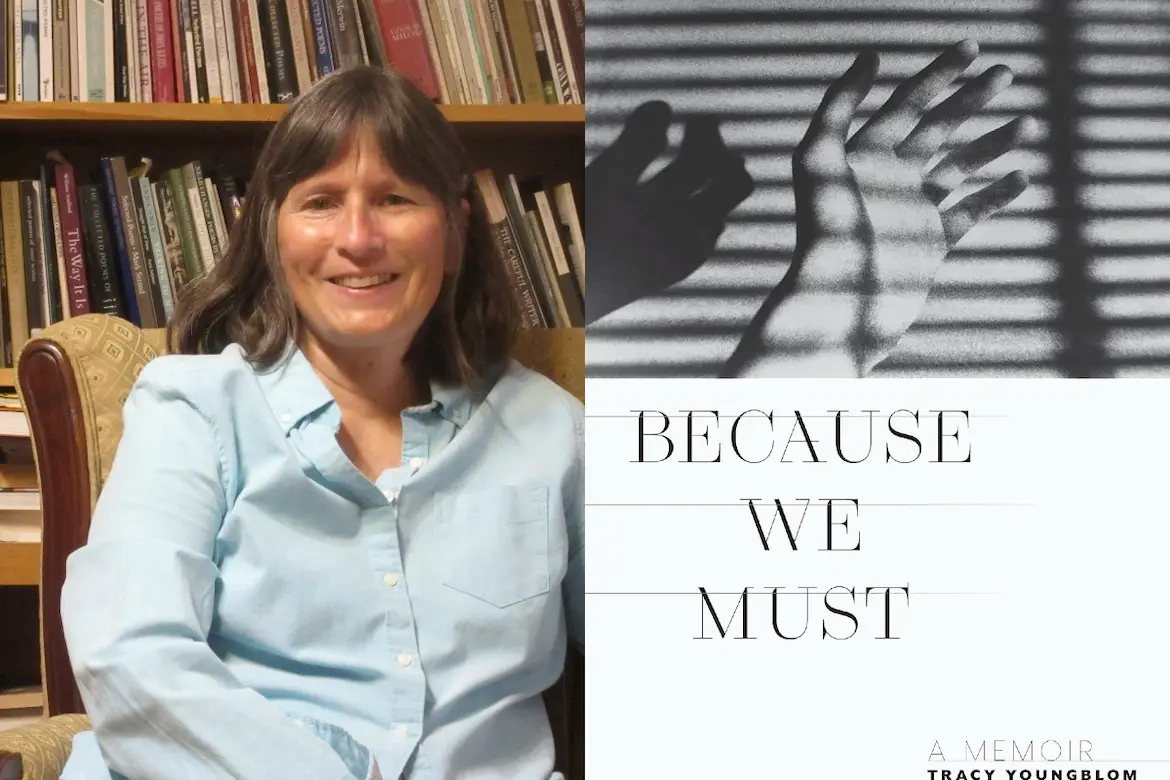

In This LitStack Author Interview of Tracy Youngblom

On Motherhood, Moments, Manuscripts, and Her New Memoir, Because We Must

In 2015, Tracy Youngblom’s son Elias was tragically hit almost head-on by a drunk driver on his way home. While Elias miraculously survived, he was rendered blind from the accident. With great strength, bravery, and humor, Elias began the journey to recovery and adjustment to the dramatically new path ahead. While this book surrounds Elias’ accident and recovery, Because We Must is also the story of Tracy’s journey to learning how to support her son and begin to heal herself after the accident; a story about motherhood and the struggle to live and grow through grief.

At the end of her book, Tracy leaves readers with a true-to-life open ending: the future is unfolding for her son, Elias, but her path seems somehow even less clear—what will she do now that her son has again spread his wings into independence? Where will her grief, in its many forms, go?

Just a few days after the official launch of her memoir Because We Must, I was fortunate enough to catch a moment with Tracy to discuss her book, as well as the topics of motherhood, love, grief, life, and writing. In this conversation, Tracy and I discuss what came next following the book’s conclusion, and discuss the experience behind the writing of this book and what writing means to her.

The Journey, Continued

R: Thank you so much for joining me today—I really appreciate your time in being here, and I know this must be a pretty busy time for you, seeing as the book was just launched this last weekend. I first just wanted to start by checking in, and seeing how you and your family are doing.

T: Yeah, thank you—I’m doing well. You know, it’s just very soon—soon to the ten year anniversary of the accident. But I think, all things considered, we’re all doing well. Elias has adjusted and is happily married and has a full life, and doesn’t live very near to me; like a three and a half hour drive. So, I mean, I speak with him, but see him maybe three or four times a year. And so maybe it’s a little bit harder on me, but, I mean, it’s hard to be too down about it because he’s just really doing fine.

R: That’s great to hear, but also sounds difficult for you. It reminds me of how your book concludes, and I’m curious to hear your perspective on that part. The ending is sort of open, and definitely has a bittersweet quality.

T: Ironically, I think writing those later chapters was the most difficult part. That was harder to do than writing about the accident, in some ways, because it was harder for me to go through that. I mean, I had thought, I suppose, at the beginning, well, he can’t see. He’s blind. He’s probably gonna live here for a really long time, and that didn’t happen. And so I think I had this idea that he was just going to be around, and he wasn’t. And I think that was hard for me.

But, also, I think it could also just be fundamentally being a parent. We have conversations, we do all kinds of things together, but every once in a while, I think, he can’t see me. It’s just this that’s gonna be the reality for me. You know, I think it was harder as that reality sunk in. And then, like I said, he moved on with his life and that I was still sort of in this [grieving period]. I was still trying to adjust, but also I didn’t and don’t want to do anything to drag him down. I mean, I’m not calling him all the time and saying, oh, this is really hard to take.

R: Definitely, and I think that part of the book is so powerful, when you talk about texting him and not getting a response back and just being like, well, that’s kind of the way it goes—sad, but also proud and wanting him to be happy. It actually contextualized conversations I’ve had with my own mother about that. And I cried when I read that part and called my mom.

T: Yeah, and I think that’s great! I mean, not great that you or your mom is sad, but that that’s universal. Like, that piece of it is just mothers and kids. That’s just a normal part of the journey. Because I’m not their first priority anymore, which is normal.

R: To me, that also seemed difficult in this context—it’s maybe the most “normal” part of your story with your son, but it’s heightened by everything that you had both experienced over the years. “Normal” can be challenging to try to get into the rhythm of after being in survival mode. That’s something that I also noticed in the way you analyzed the ways that your life had changed to accommodate grief.

You’re incredibly self aware down to the specifics—you write about control: control in your schedule, not being as active as you used to be, and your diet, like eating the same breakfast every morning. You mention the way this protected you in a way, while you were managing all the change and the grief coming your way. And also at the same time, you mentioned not wanting to have that change you forever. How would you say things are now?

T: You know, I think that I continue to process all of that in myself. I do think that I’ve learned to respond to things in a way where I could sort of control my response. I know I talk about breaking down, falling apart, whatever that means. I felt like I developed these habits where I wasn’t going to let that happen. I mean, that in and of itself I don’t think is bad.

I think when I started to have a concern was, do I have no spontaneity in my emotional life anymore whatsoever? And I don’t think that’s true. I mean, the book goes on for five years following the accident, but I feel like I am continuing in reflection about that.

I think it’s okay to have routines, and I think it’s okay to understand that some things are going to be emotional. I don’t wanna be stiff—like, emotionally stiff. So I do think about that. And I’ve been able to work on relationships more with my other kids since, just because in that time, not that they got pushed to the side, but the focus wasn’t on them.

I feel I’ve been able to be more involved in their lives, and that’s really good. I’m still aware of that impulse in me to be like, oh, not now. I’m not gonna feel that right now. But I think I’m also finding outlets, because I don’t think it’s necessarily good to live that way all the time.

R: Definitely, trying to find balance is a constant undertaking—balancing being open emotionally and surviving the day, control and spontaneity, grieving and moving forward. That makes me think of that Milk Carton Kids quote that you put in the book, “Freedom comes from being unafraid of the heartache that can plague a man”. How does that sort of resonate for you now?

T: I was just listening to that CD not too long ago! I think you’ve got to think okay, it’s happened, but if I can’t move forward…none of us can go live our lives being afraid of the next terrible thing that’s gonna happen. Like, I can’t do that. There’s only so much you can control.

That would drive me into the interior of myself, and I would probably never come outside if I allowed that to take hold of my life. So I still think that that quote is true. And like I said, anything can happen in a week. Now I know it, viscerally—something can happen suddenly and unexpectedly. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen all the time. So I really have to try not to dwell on that.

Motherhood, Longing, & The Unknown

R: That reminds me of the role of the parent we sort of discussed earlier with children becoming adults and that lack of communication that seems to come with independence and priorities shifting…maybe a sense of fear that seems to come with that role of a parent as well? That feeling of wanting to protect your children, and not knowing what the future holds?

It’s so interesting to hear this from your perspective because at the same time reading it, I was wondering how Elias is doing with that fear, too. Throughout the book, he manages to stay so optimistic and motivated to work out the life that works for him, and the future that he wants for himself, which is incredibly impressive. He seems to not really deviate from what his original goals were, but rather adapts them to fit.

T: Yeah. You know what? I believe that he probably does have moments of concern too. But I also think Katie, his wife, and him just have a great relationship. So I don’t know, I think if he had those fears, he would tell her and they could figure out a way to talk about it.

The only conversation that’s related to that that I’ve had with him is that we keep an ear out for medical research that might be going on as far as optic nerves and things. And he was going to participate in this trial one time, but then he had to go live somewhere for, like, six weeks. And he said to me at that time, “You know, I don’t know if I wanna get my sight back. Maybe that’s not ultimately what I want. I’ve had all this time to learn how to live with this. I have a good life”.

I just thought that was interesting. It’s not exactly like a fear, but it is sort of a weird kind of fear. What if I can see and I don’t like what I see?

R: Hmm, interesting—maybe the known being better than the unknown. How does that feel for you to hear that from him?

T: The things that he says like that have been a steady thing throughout this time. And I have really mixed feelings about it. I am very proud of him for being able to be so fearless. Fearless isn’t even the word. Just accepted it and made the best of it. I am very proud of that, but I’m just reminded also of the magnitude of it. And I would want him to be able to see again if he could. Of course, I would. And so it’s just that grief that’s never going to quite go away. But sometimes, he’s just the king of saying things that stab me in the heart a little, you know?

R: That seems like the job of us kids sometimes, doesn’t it? Elias really does seem incredibly motivated to love the life he has, and it is so inspiring to read, but I can certainly see how that would complicate things for you as far as grieving yourself. I was also interested in what you talk about in the end of your book, about longing and love the way it exists in your relationship to your son. Would you be able to expand on what this means for you?

T: Yeah, it definitely still exists. But maybe it’s a little bit less pronounced just because we’re all moving forward. We have to move forward. At that time, when I wrote that, he was moving. It was very sharp. I had all my memories right there, and the whole rhythm of my life involved him and being around and driving to and from places and so it was hard to know that that wasn’t going to be me anymore.

That might be the parents’ lot, too. To feel a longing for something—what it is, I’m not sure. When you can’t move to your children or they can’t move to you; that’s sort of not entirely painful, but maybe the whole bittersweet thing again, you know, that everything’s gonna keep changing. We’re not going to have the same relationship we did when he lived here for those five years. We’re going to have a different relationship.

So I guess I still feel this sense of longing! I did just say to all my kids, you all should live on my cul de sac. And they don’t think like that, but it’s just the little daily things that I want sometimes where I want things to be different. I’d love to bake cookies and go run across the street and give them to them every day, if I could do that.

R: My mom is always trying to sell me on her neighborhood, too! I think maybe it’s the feeling of still seeing my sister and me as kids she wants to take care of, but we’re also adults—we’ll always be both, but it’s not as simple as just one or the other. Do you feel like that’s something you’ve noticed sharply particularly in becoming a mother—that sense of longing?

T: Yeah. I mean, even when my kids were little, you just wanted the best for them. I think it’s the difficulty of being a parent, but it’s the best job of my life. But, yeah, I do think that longing comes with it.

The Process of Writing, The Importance of Moments

R: I would also love to speak with you about the process of actually writing this book. In the beginning, you write about your initial response to Elias about writing this book, which is actually to reject the idea completely. And because writing can have a way of sort of condensing time, and considering the challenges of writing about something so personal, I’m curious—how long would you say it actually took you to write this book?

T: I started doing some writing that fall, the fall of 2015. But I wasn’t thinking I was writing a book. I was writing to feel my way forward, to express the difficulties of [grieving]. I was telling this story because I had the book launch on Saturday—I know I actually wrote quite a bit that fall because, in early January of 2016, not even a year after the accident, we had a ransomware virus on our home computer, and lost everything I’d written about the accident. I feel like at that point, I was like, oh, I have to recreate this. I was writing about some stuff that might be pretty interesting.

R: Oh no! But that’s interesting, that being a point of more active choice to be writing this book. So that moment was sort of a turning point into something beyond writing just for yourself?

T: Right, at that point is when I thought, well, maybe I’m going to try to write a book. Maybe I’m going to try to do that. I had a first draft of a manuscript within two years of that. But when I compare that to how it ended up, I’m glad I kept writing. The book covers about a five year time period, so almost to 2020. And I think a lot happened in those other years.

R: A lot happened in those other years you include, I agree. The beginning of your book is largely focused on the accident, but as we move into the middle and end, it becomes a lot more focused on grieving and recovery, for both you and Elias.

T: Yeah, so I’m glad I didn’t have a manuscript and said, oh, I’m done writing. I just kinda kept going. So in its final form, writing took about eight and a half years.

R: What sort of pushed you over the edge into writing it, would you say?

T: Well, I do think once I started writing it again, like, in January 2016, I found writing prose doable. I almost felt like, I’m primarily a poet, but I don’t know. I just couldn’t write poems. I didn’t know how to write poems about that [the accident]. But I found that I could write prose about it.

R: And when did you know or have an inkling that you were going to turn that writing into what it is now?

T: I think once I kind of showed some parts of it to readers. I have friends who are writers, and I got some positive feedback. But it isn’t whether people like just the story, because it’s an amazing story, but if people think there’s anything in the writing that’s worth pursuing. But eventually, with that feedback, I thought, okay. Well, I’ll see what I can do.

R: I know that you’d written a good amount of poetry before this book, and had published work. So how did you find that process of working on a piece of prose rather than poetry? How did that feel for you, and was it different or in any way format-wise difficult?

T: No, it didn’t feel too different. There was a certain sense in which writing sentences and paragraphs was much easier for me than directing poems because directing poems is, like, I don’t know. What is it gonna look like in its final form? It’s just different visually. So I found the drafting of these essays a lot easier.

What was more challenging was shaping it into a manuscript. That was a challenging process because I think, especially with my last couple books of poems, even before I did any writing, I had an idea. I’m going to write this group of poems about X. And I did that. And I didn’t really know, when I was first writing and even first putting a manuscript together, I didn’t know how to describe what I was writing about. I could say, oh, I’m writing this book about the accident, but I didn’t really know how to describe the shape it was gonna take or the arc of it. So that took me a lot longer to get to.

R: Yeah. Talking with you about structuring your book is really interesting because in your introduction, you talk about Abigail Thomas and the way she wrote her memoir, What Comes Next and How to Like It.

T: Yes, Abigail Thomas! And once I started doing more writing for this book, I went back to that book and read it, like, two or three more times. It’s super short chapters, it’s fragmented, and it’s a whole bunch of different stories, and then you don’t kind of see how they all fit together until the end. It made me feel like, oh, I could do something like that. That seems doable to me.

R: Definitely. And I can see that in the style of the spatial bursts, and the understanding of the story as it comes together. I think this style allows you to look into some really important parts of the journey in a natural way, because, obviously, the story has to be condensed. Writing prose, there has to be a lot of condensing of what is actually happening and figuring out a way to do that where it makes sense is extremely difficult.

T: Yeah. And I don’t know at what point I realized this, but I read a lot of traditional memoirs, and I just wasn’t sure that I could do it in that way. Like, I didn’t know that I could just start at this point in time and go through, so having the shorter chapters and having some different forms, but they’re titled. I wasn’t sure if I could have chapter one, chapter two, chapter three. So whatever that means, but that’s kind of how it all came together.

R: It reminds me a lot of poetry, really, the flow of things.

T: Yeah, I actually can see that. You know, just with repeating images or the sort of shape some of the chapters slash essays took. Like, a collage form that felt very much like poems to me too.

R: That style feels a lot like the flow of memory itself, fragmentary and collage-like. It’s a memoir about your experience and memories and feelings. At the same time, you have these moments where you include memories almost outside of yourself. I’m thinking in specific, the chapter about the green beans and relating that to care and adapting and growth. I think that there is so much meaning to every piece that you’ve put in as part of this greater whole. So I was just curious if there’s anything that you wish you had added or anything that didn’t make it into the final manuscript, but you still think about it?

T: No. I mean, there were definitely other pieces that I wrote and didn’t include. But that was more because I thought the writing wasn’t as good. In the end, I wrote the hard things, some of my realizations. And I didn’t find it that challenging. I think I always wanted to write about and include these moments and realizations because I think moments are what everybody’s life is. That’s where the significance happens, just in moments.

Writing & The Influence to Write

R: I love that, that feels very poetic—life being made up of these fragmented moments, a collage. You seem to have such a clear idea of what you want to write, and I’m curious about the why of why you write. In the beginning of the book, you allude to your relationship to writing in a way that insinuates that you write to give something to the world. I’m interested to see if you could expand on that and your intended purpose in writing.

T: I thought what I could not give the world was hope. You tell some stories to offer hope at the end. I was still adjusting to learning that Elias would remain blind. I’m not sure if this was conscious, but as I wrote, I thought, if I can communicate how he dealt with this—his resiliency—that was hopeful. Even to write, look at this kid I’m lucky to have, how he responded. I thought that might encourage people. I don’t think anybody knows how they’re going to respond. Eventually, I focused on myself. But earlier, I focused on him, when he was living here and all these little things that would happen when we would go somewhere.

R: I’m interested in that shift in focus you describe—did you feel any kind of perceptible shift in the narrative when you were writing, when you talk about focusing on him versus focusing on yourself?

T: Before he moved and during the adjustment and transitioning phases, I saw him often, and drove him around. But then I was left alone to deal with my own stuff. At a point I was well aware that he was doing better than me. My reality was very different from his. And so I felt that writing much of the content of the second half of the book was about realizing my new reality. I didn’t burden him with it all. Now that I’ve written the book, he’s gonna read about it and whatever. But I was just thinking, I have to tell my part of it, too, and my part is not as upbeat.

R: In the beginning of our conversation we talked about the purpose of writing at first to just sort of work through your feelings. And then as time goes on, it would make sense that as you’re writing about Elias, then you begin also talking about your difficulties as the journey continues sort of internally for you. So with writing in general, did it always begin as writing to work through your feelings? When did you start writing, and when did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

T: My first memory of thinking writing was kind of a cool thing was when I was in the fifth grade. Our teacher had us doing a poetry unit, and we read all these books. I still have some of these books, and we wrote some simple poems and illustrated them. And I just remember thinking, this is so fun! And then, by the time I was in high school, I was writing more poems.

I discovered contemporary poetry through some teachers that I had, and I was writing more poems. So I feel like by high school, I was more or less committed to writing. I did the literary magazine in high school, then I went to college, took writing classes, and submitted works for the college literature magazine. So I feel like by that time, I was pretty committed. And I don’t care very much now how I label something when I’m writing. It doesn’t matter to me if I say it’s a story or an essay or a poem. I don’t care.

R: That’s interesting! What was it that pulled you towards poetry in the beginning, do you think?

T: That’s a really good question. I remember very vividly in high school, there were these volumes. They were called, like, 20 Minnesota Poets or something. And the poems, they just suddenly struck me as, well, these are really just about real life. These poems are just about people’s lives.

Not rhyming and all that, which is fine for me now—like, I love form too, but at the time, they just felt very accessible, and it felt like there was something about them that felt so true. And I thought, well, I could do that. I have things in my life that I could write about that are true, even though they’re just ordinary normal things. And then I met some writers, in particular, Deborah Keenan who still teaches and writes locally. Again, that just made me feel like I could do that. You know, I could just look at my life and write about whatever. And just reading! Writers read, goes the idea.

R: Other than the compilation book of Minnesota poets, would you be able to share a favorite memorable or influential book for you?

T: Moby Dick, which I just reread recently!

Thank you, Tracy!

A massive thank you again to Tracy for joining me for this conversation—I am incredibly grateful for her time, vulnerability, and generosity in sharing her experience and wisdom with me. Looking towards the future of her writing, Tracy is currently working on both more prose and poetry pieces as she continues to teach at Anoka-Ramsey Community College. To check out her previous work and upcoming events, please visit Tracy’s website. To read more about her memoir, feel free to check out our review linked below.

~ Rylie Fong

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our LitStack Reviews for our recommendations on books you should read, including reviews by Lewis Buzbee, Lauren Alwan, Allie Coker, Rylie Fong, and Sharon Browning.

About Tracy Youngblom

Tracy Youngblom is a Minnesota-born-and-raised writer and teacher. She is happiest when outside, sifting her fingers through the soil in her gardens or hiking trails in her neighborhood or the woods. She earned an M.A. in English from the University of St. Thomas and an MFA in Poetry from the Warren Wilson Program for Writers. She has been teaching college English since 1996, at a variety of schools, but has been happily settled at Anoka-Ramsey Community College since 2004.

She has published two chapbooks of poems, two full-length collections of poems, and one memoir. In addition, she has published poems, stories, and essays in journals including Shenandoah, St. Katherine Review, Cortland Review, Blue Mountain Review, Briar Cliff Review, Bloom, North Dakota Review, Weave, The Phoenix, Potomac Review, Poetry East, Minnesota Monthly, and other places.

You can connect with Tracy Youngblom on her website.

Sources: Publisher, Tracy Youngblom

Publisher: University of Massachusetts Press

ISBN: 9781625348524

Pub Date: Mar 7, 2025

Titles by Tracy Youngblom and Others

As a Bookshop, Malaprop’s, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Audiobooks.com, Amazon, and Envato affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.