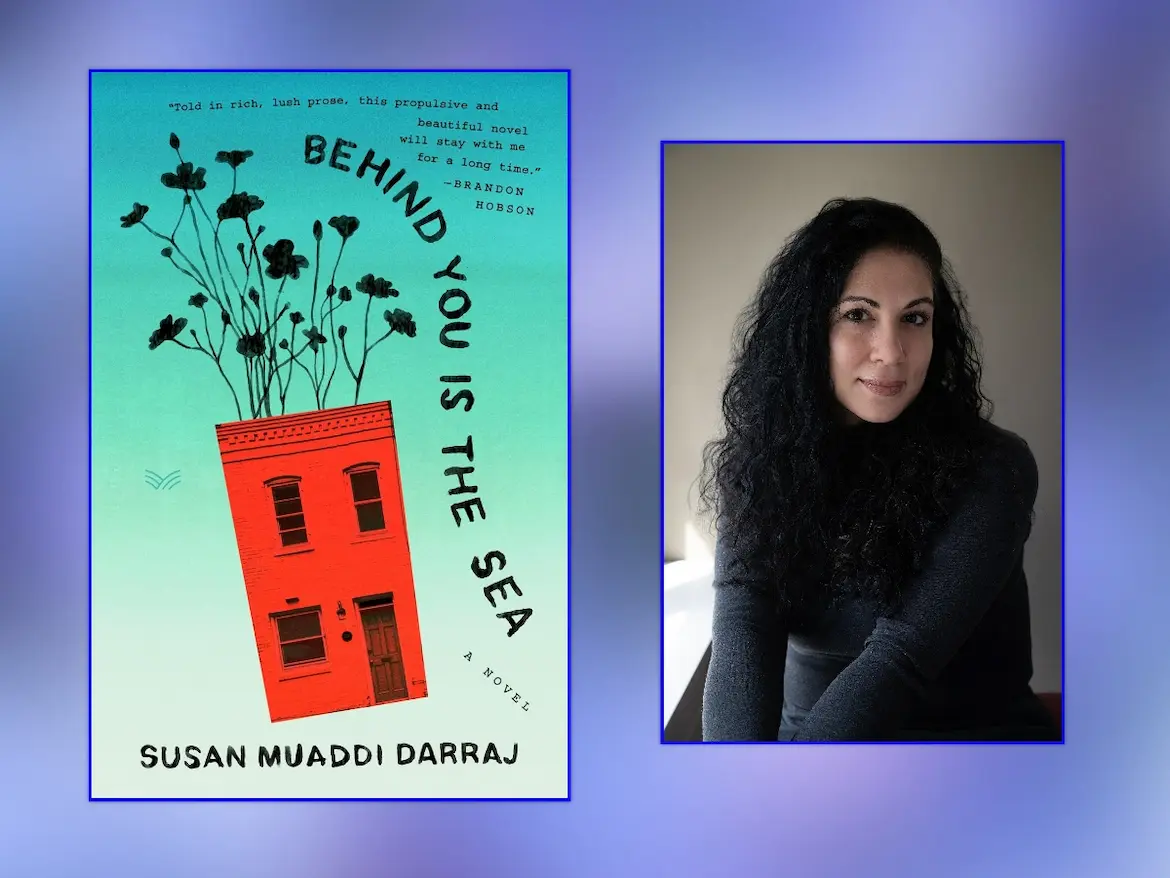

LitStack is proud to give you this review written by guest contributor, Michael Collins, who offers attention and insights into Susan Muaddi Darraj‘s debut novel, Behind You Is The Sea.

In This LitStack Review of Behind You Is The Sea

Behind You Is the Sea by Susan Muaddi Darraj

“Behind you is the sea. Before you, the enemy,” reads a plaque in the office of a Palestinian-American businessman. “You have left now only the hope of your courage and your constancy” (104-5). The scene’s multiple contexts for the quote, half of which forms the title of Susan Muaddi Darraj’s most recent novel, provide one opening into the book’s seamless layering of histories and contemporary perspectives.

The quote itself is from a speech by Tariq ibn Ziyad during his invasion of Spain, after he “burned his men’s ships at the harbor so they couldn’t sail home; he’d known they were scared, so he made fighting their only option” (105). This mixture of fear and resolve manifests differently in the books’ many characters, though they all share with the image a sense of negotiating a relationship with a removed past in order to move into an uncertain future. In the story it is being read to Demetri, a wealthy real estate owner who can’t read the formal Arabic on the plaque himself, by Maysoon Baladi, a young housekeeper who briefly moonlights as one of his many extra-marital affairs. The totality of the scene presents how the novel interweaves issues of class and gender with those of culture and history, connected by a subtle understanding of humans’ often flailing attempts to meet needs they struggle to understand. Culture and tradition are passed down in many ways in the book, but always refracted through these psychological experiences—ranging from conscious values to unconscious compulsions—of characters who are also shaped by age, class, gender, and profession.

Novel Form and Characters

The novel comprises a sequence of short stories whose Palestinian and Palestinian-American narrators are characters in some of the other stories. Beneath these surfaces, the novel weaves the perspectives together as contributions to a deeper meditation on the many constructive and pathological tensions between individuals and communities. These symbiotic aspects open to the reader, through particular lives of a community that lives concurrently in multiple spheres, a perspective on life in a global world that many of us can relate to regardless of background, if we read with quiet eyes.

This accessibility, in part, owes to the delicate, cumulative way in which the novel evokes the complexities of community itself through the dynamic array of characters Darraj releases to us through their unique senses of humor and outrage, their incisive insights into one another, and their personally resonant images and memories that evoke the poetic aspects of their souls.

The New Within the News

The novel opens windows into Palestinian experience through events like the intifadas, recognizable to those who follow the news, but far less commonly understood in experiential depth. Rita, a Palestinian woman, reveals one horrible aspect: “A lot of the girls who got arrested…we got hurt in jail. Not just beating us. More than that” (232).

A townswoman offers one motivation: “That’s what they did to punish the girls’ brothers. To keep their fathers and uncles off the streets.” (227). Yet, for the survivors themselves, more subtle effects of these crimes ensue upon returning home: “When I came out, I was a hero for a month. Everyone came to my parents’ to welcome me back. And I was so sick, I didn’t notice at first. But soon, I started to see that I was like an infection. Nobody wanted to catch me” (233).

All of this is further contextualized by the town’s pervasive fear of “the large white homes on the hillside, flanked by watchtowers, bordered by security fences,” homes of Israeli settlers “who wanted to push these people out, like pioneers pushing out Natives on the frontier” (219-20).

We learn of these dynamics through the deciphering of Marcus, a Palestinian-American who is piecing things together for himself as the story unfolds, at times through tentative conversations with locals that evoke the acute sensitivity of both the information and its communication. The reader, through Marcus’s experience, gains some insight into the lives behind news images. Perhaps the most important insight is the sea of things we don’t know present beneath the surface waves of the news story.

Perspectives on “Popular” Culture

Pop culture provides an access point to Layla Marwan’s experience of her high school’s production of Alladin, in “Gyroscopes.” The story explores how insensitive the self-proclaimed champions of cultural sensitivity can be when Layla raises concerns that “it’s a movie that has a lot of stereotypes about Arab Americans,” to which the director responds, “’Impossible. It was written in a time when there was no such thing as America,’ he says, laughing, and everyone else laughs too because now it’s awkward” (125).

The story unnervingly shows how the students rally behind the teacher’s defense without much critical examination, even using the rhetoric of inclusivity: “But he’s going on about being inclusive and how we have to listen to everyone’s voice, except he’s just ignored mine” (126). This may be a particularly ironic case, but the novel subtly reaffirms throughout that the support of diverse voices can only arise by actually listening to those actual voices, not overarching narratives that coerce themselves over the lives of individuals.

Humor and Resilience

More compelling, however, are the strategies of resilience modeled by Layla’s mother and Layla’s own humorous self-defenses. Her mother advises, “sometimes people just have to take your word for it. It’s like someone stepping on your toes and not moving off. Do you really have to explain how the pressure is causing you pain?” (129). However, she balances: “You don’t have to prove it […] Or agonize over how to explain it” (129; italics original).

Likeably incisive Layla takes this to heart—her own heart—when a classmate encourages her to try out for a part in the play because, “you would look authentic. If that makes sense.” She quips, “It doesn’t make sense, because she’s a cartoon” (131). Her humor cannot resolve the deeper levels of intolerance in the story, but her awakening of resolve to be herself despite what others expect is an essential seed of resilience nonetheless.

Fear and Intolerance

Beneath the level of identifiable mass media touchstones, the stories take us through the fears and misconceptions of various perspectives that lead to different presentations of intolerance. The interactions of Mr. Ammar, a wealthy Palestinian-American businessman, with his new in-laws at his son’s wedding reception show one poignant example:

“Gotta always ask, you know. This way the culture doesn’t become a problem.” He was only half-listening to Mr. Ammar anyway, waving at other guests. Before they reached the front of the room, the man stopped and waved his hand around. “Like some of your guests here, they’re wearing head scarves. That’s not gonna be something Ray surprises my Ellen with, right? In a few years?”

“We are not Muslims.” Mr. Ammar’s head started to hurt. “These are our friends.”

“Right.”

We can empathize with Mr. Ammar’s weariness with what are obviously exhaustingly pervasive assumptions, both that all Arabs are Muslims and that the man has the right to ask for assurances that the cultural differences he fears will not lead to “surprises.” However, the older generation of characters to which Mr. Ammar belongs also stubbornly uphold sexist “traditions” that harm several female characters: “[H]er marriage was over. Because she’d married a man who believed people could be ruined” (84).

Sharing Words and Views

One recurrently gracious gesture is to treat each meeting between individual characters as a unique dialogical opportunity for different versions of cultural perspectives to engage with one another. Some of them are provisionally transformative. Others, like these, are equally valuable in an apparently negative way, as examples of harmful patterns mended only, as possible, by bearing witness.

These interpersonal micro-evolutions often take place within the Palestinian-American community through the sometimes confusing co-immigration of culturally important Arabic words. Haram is one recurrent example: “Getting knocked up is haram but abortion is more haram, according to Mama” (89).

However, Marcus’s evolving relationship with his wajib to bury his father in Palestine, which at times involves a deepening understand of what it practically entails, presents a consciousness deepening experience: “The old man hadn’t spoken to Marcus for five years, and yet strangely enough, what had kept Marcus awake was white-hot anger, fueled by two fears: that he’d be unable to fulfill this wajib, and that his miserable, broken father, who hadn’t seen Palestine for fifty years, might literally crumble before finally returning” (212).

The use of Arabic words that cannot properly translate without cultural context also connects the stories with a more common modern experience of encountering in daily life aspects of others’ backgrounds that we don’t entirely understand—aspects that the people using the words may wonder about themselves in different ways. Experiencing such intercultural phenomena as readers allows us to slow them down and reflect on how much we are missing, how often we may make assumptions in those gaps.

Cultural Differences and Individual Perspectives

Cultural differences also obstruct communication in many characters’ interactions. Mr. Amaar is galled by his daughter-in-law, giving his son an American name: “It burned him up! Raed meant ‘pioneer,’ he who blazes a path—that was his son, so smart and capable and clever. He had rejected the family business and left it to his brother, Demetri. Instead, he’d gone into law, and now he made a quarter million a year. Why would she reduce that name when he and Nadya had chosen it so carefully?” (48; italics original).

His outrage contains valid critique of ridiculous things Americans say that may pass notice simply because of their prevalence: “’Ray and I share a culture—we’re both Leos,’ like it was such a big fucking deal. One-twelfth of the world are Leos, Mr. Ammar wanted to shout at her every time she said it” (49).

Much younger Maysoon has a similarly visceral reaction to Mr. Amaar’s son and his failure to understand his own comparative privilege: “’Wow,’ I murmur sympathetically, wanting to tell him Reema works two jobs in one day and comes home so broken and tired she can’t eat. Arabs are ridiculous; even if they live a dream life, they want to star in some tragedy. If there is no tragedy, they imagine one” (105-6). In both cases the individual’s boundaries foster cultural critique, the younger characters tending to critique both cultures in their attempts to negotiate between them.

Individual Strength and Transformation

One positive result of these tensions occurs when characters discover their own innate strengths within the uncertainty of their prospects. Reema, for example, finds strength in her gradually discovered emotional intelligence:

Americans like to talk about everything, I know. They like to share their feelings, like purging old clothing or dumping clutter. But when you’re like us, you purge nothing. You recycle or repurpose every damn thing. Nothing is clutter. And as I stand here, watching my father die before he ever really lived, all I can think about is how I’m going to use these feelings I’m having now. I need someone to love, the way I love Baba. I can’t love Mama because she’s a ghost, and my sister is so young that . . . well, I can love her, but she may not always want it from me. Torrey is someone I can love, but he may not always be able to give it back, either. Not with the steadiness I need.

Behind You Is The Sea, (13)

On the other hand, Hiba finds seeds of healing from painful college experiences in the personalized traditions of her grandparents: “Her grandparents spoke in casual poetry, dropping phrases like “you’re blooming today” and “you bury me because I love you so much.” They always, always, always called her habibti and ya ayooni. My love. My eyes. The fact was that she wasn’t used to this, this awkwardly normal way of discussing intense emotions” (141-2).

Tradition, valued personal experience, and daily practice intertwine seamlessly for her grandmother: “We lived during three wars. Lentils kept us from starving. Your Seedo and I—we love eating them. It reminds us of those days” (160). The novel leaves a quiet but persistent impression that the co-evolution of cultures takes place in an ongoing way within the lives of individuals, each of whom must find their own path between them.

Image and Healing

Fittingly, the novel reveals Hiba’s process of incorporating this lifestyle and worldview through an image-experience, the implication being that it will resonate with her over her time of healing: “Hiba continued steadily picking, watching how Sits’s fingers worked so swiftly, flicking through the dry beans, clicking and shifting them across the wide aluminum pan, separating out the stones that would hurt you from the lentils that could save you” (160). Samira, a successful lawyer with a manipulative family, reincorporates an image similar in personal resonance while beginning her own family with an American man:

Now, with the baby, with Baba fading, with ever-present work stress, now was a time to lie on the weak surface of water, to trust that its fragility could nevertheless keep her afloat. It could even, despite its transparency, carry her great distances.

One afternoon, as she and Logan stood together, browsing the bookstore for baby books, she observed him. How beautiful to be having not just a baby, but Logan’s baby, she thought as she watched him leaf through a book, pause on a page, and shake his head in wonder.

Behind You Is The Sea, (202)

In addition to mirroring the flexible openness of its more grounded characters, these images also require the psychological patience of this same grounding, an open-ended recursive practice experience over time, during which they accrue depth by adding perspectives and insights.

This rather poetic feature of several of the stories’ endings corresponds with the novel’s overarching openness in channeling such an array of characters without judgment. In valuing characters’ touchstone images, it displays a profound respect for the right of individual character to express itself in a self-determined life path, the whole of which is to be valued as both a process of improvisations demanded by the practical world and a sustained focus on its own realization. This book, among other things, is a guide to perceiving others with such generosity, the outcomes of which can be as shocking as Mr. Ammar’s concluding realization, “I’m okay. I’m listening” (61).

~ Michael Collins

All Quoted Excerpts are from Behind You Is The Sea

HarperVia

January 16, 2024

Paperback; 256 pages

About Susan Muaddi Darraj, Author Of Behind You Is The Sea

Susan Muaddi Darraj is an award-winning writer of books for adults and children. She won an American Book Award, two Arab American Book Awards, and a Maryland State Arts Council Independent Artists Award. In 2018, she was named a USA Artists Ford Fellow. Her books include her linked short story collection, A Curious Land, as well as the Farah Rocks children’s book series. She lives in Baltimore, where she teaches creative writing at Harford Community College and the Johns Hopkins University. Her new novel, Behind You Is The Sea, was published in January 2024 by HarperVia.

You can find and follow Susan Muaddi Darraj on her website, on Facebook, Instagram, on her LinkTree, and LinkedIn.

Other Titles by Susan Muaddi Darraj

About the Reviewer, Michael Collins

Michael Collins’ poems and book reviews have received Pushcart Prize nominations and appeared in more than 70 journals and magazines. He is also the author of the chapbooks “How to Sing when People Cut off your Head” and “Leave it Floating in the Water” and “Harbor Mandala” and the full-length collections “Psalmandala” and “Appearances,” which was named one of the best indie poetry collections of 2017 by Kirkus Reviews. He teaches creative and expository writing at New York University and has taught at The Hudson Valley Writer’s Center, The Bowery Poetry Club, and several community outreach and children’s centers in Westchester. He is the Poet Laureate of Mamaroneck, NY. You can find and follow Michael Collins on Linkedin and his website notthatmichaelcollins.

Titles by the Reviewer, Michael Collins

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our other LitStack Reviews of books you should read, as well as these reviews by Lauren Alwan, and these reviews by Sharon Browning.

As a Bookshop, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Audiobooks.com, Amazon, and Envato affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

You can find and buy the books we recommend at our Bookshop by clicking our LitStack Recs banner.