A Definitive study of Alfred Hitchcock, by Francois Truffaut, trans. by Helen Scott (1966)

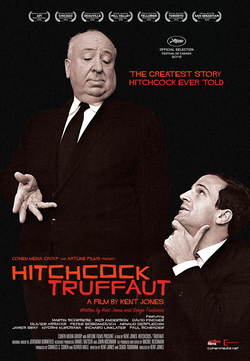

& Hitchcock/Truffaut, a documentary film by Kent Jones (2015)

Before he began directing, Francois Truffaut was a film critic, and before that, a voracious viewer of films. A director and a founder’s of the French cinema’s New Wave began his movie habit at the age of eleven. From then on, films quickly became an obsession—seeing them, reading about them, logging filmographies. Truffaut often saw three to four films a day, and repeatedly saw his favorites as many as ten to twenty times. This immersion into the art of film comprised Truffaut’s education, one he brilliantly parlayed into work as a journalist and film critic for Cahiers du Cinema. In 1954, at the age of twenty-two, he published the ground-breaking essay, “A Certain Tendency in the French Cinema,” which formed the basis of what would become auteur theory, the director as author.

A fascinating aspect of the self-taught Truffaut is his youthful aspiration to interview directors whose work he revered. He did this not out of ambition, but as a means to understand how the films were made, to unlock his heroes’ secrets. With his lifelong friend Robert Lachenay (who also became a film critic and documentary filmmaker), the two systematically contacted directors (most of whom agreed to be interviewed), guilelessly offering “free publicity” in return for participation.

One of the first American films Truffaut encountered was by Alfred Hitchcock, the 1948 film Rope. At the time, Hitchcock wasn’t garnering the rave reviews he would for films like Strangers on a Train or Rear Window, but Truffaut was instantly captivated, recognizing in the English director’s work the qualities he loved most about film: the nod to film noir, the auteur’s view, the careful design in Hitchcock’s technique.

By the mid-sixties, Truffaut had achieved his own fame with the now-classic film, The 400 Blows, which won the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Director. Soon after, Truffaut, a longtime admirer of Hitchcock’s work, wrote to him. “There are many directors with a love of cinema,” Truffaut wrote, “ but what you possess is a love of celluloid itself.” Hitchcock was smitten:

“Dear Mister Truffaut,” Hitchcock wrote back, “your letter brought tears to my eyes, and I am very grateful to receive such a tribute from you.”

The interviews took place at Hitchcock’s office at Universal Studios in the summer of 1966. With Truffaut’s longtime colleague Helen Scott serving as translator, the conversations were recorded and transcribed into the now-classic book A Definitive study of Alfred Hitchcock. The book, copiously illustrated with film stills and storyboards, contains material culled from over thirty hours and fifty tapes, considered by filmmakers as a “bible of film literature.” a virtual master class on filmic technique and auteur theory and practice.

Their conversations form the basis for Kent Jones’ new documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut, an eighty-minute documentary version of the book that brings the conversations to life. The interviews translate to film due to the astoundingly perfect condition of the original audio recordings, combined with clips of Hitchcock’s and Truffaut’s films and commentary by contemporary directors—Wes Anderson, Martin Scorcese, Peter Bogdonivich and others, all of whom have studied both directors, and the book, exhaustively. Wes Anderson recalls after years of reading, his copy is no longer a book, “only a stack of pages.”

Truffaut and Hitchcock shared not only professional affinity, but a personal one, which is clear throughout the film. Truffaut confesses, for example, “I always watch a Hitchcock film without the sound,” and indeed, Hitchcock began his career in silent film, and that particular vocabulary of image-driven frame-by-frame storytelling forms the basis of his mature style, and made it influential for decades to come.

The two directors also explore each others process, and there are gems of technical insight. “Film contracts time or extends it,” Hitchcock says, and this can be seen again and again in scenes of violence, tenderness and suspense. For example, describing a shot in The Birds, he explains the thinking behind his choice of an elevated view of Bodega Bay: far below the town burns while a flock of birds careens on the air currents. “If you’re a long way away,” Hitchcock explains, “you’re not committed to any detail.” Great advice for the technique narrative distance even if film isn’t your medium.

Hitchcock was known for his visual style, but as Scorsese notes, he is also responsible for bringing the subject of obsession to a mass audience, and as a result, the English-born Hitchcock was the first to create an intimate film experience with the American film going public. “He’s fascinated about what terrifies him,” Scorsese observes, and the auteur-director who, like Truffaut, “wrote with a camera,” made his own personal fears his subject. For example, there’s Hitchcock’s frightening episode as a boy, where at age eight, he was tricked by his father into being locked in the local jail, to “teach him what happens to naughty boys,” and the fear of jails and policeman is palpable in films like The Wrong Man and Marnie.

On Vertigo, the documentary explains the film was lost in the 1970s and for years went virtually unseen except by a select few who had access to prints. Young filmmakers, like Scorsese, who’d heard about its outstanding visual effects and hoping to study it, had difficulty finding copies.

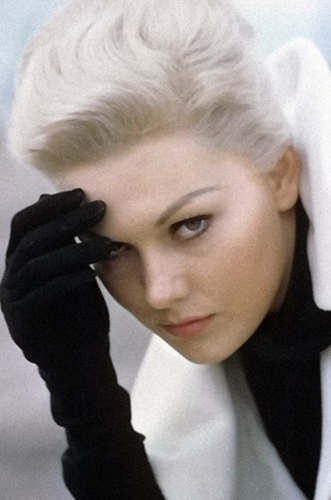

Kim Novak in a still from Vertigo

The film also gives time to unpacking the Vertigo’s plot, an often debated aspect of its success, in which Hitchcock explains, rather than explicitly connecting actions he preferred presenting “a lie that you can hang things on.” As Scorsese marvels, “It’s as if he’s saying, ‘I can’t tell you where things start and end and I don’t care.’”

Devotees of Hitchcock and Truffaut will find both the book and this new accompanying documentary essential and rewarding. Learn more about Jones’ documentary, currently playing nationwide, here.

—Lauren Alwan