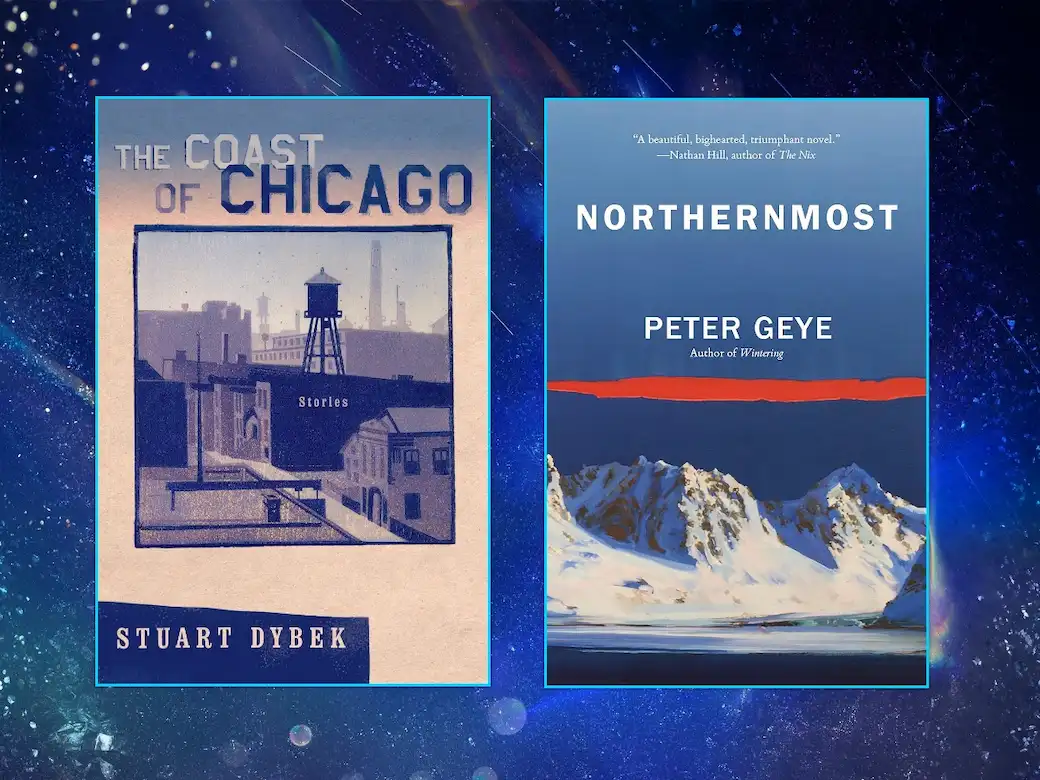

Welcome, fellow LitStackers! Let’s dive in and explore two remarkable works: the short story collection The Coast of Chicago and the novel Northernmost. Prepare to be enthralled by the unique narratives and intriguing characters these literary gems have to offer. Whether you seek inspiration or simply appreciate the art of storytelling, join us as we recommend these compelling pieces of literature. Get ready to be transported into a world where words come alive and imagination knows no bounds!

You can find and buy the books we recommend at the LitStack Bookshop on our list of LitStack Recs.

In this LitStack Rec:

The Coast of Chicago: Stories by Stuart Dybek

I can still recall first reading Stuart Dybek’s classic short story “We Didn’t” in Antaeus (Issue No. 70, Spring 1993), dumbstruck by the beauty of the images—the teenagers on the beach tangled in their Navajo blanket, the coconut suntan oil and lip gloss-colored lake along the beach at day’s end, when “only the bodies of lovers remained, visible in the lightning flashes, scattered like the fallen on a battlefield…” *

The Chicago-born Dybek has published five story collections, that range from the novel-in-stories, Paper Lantern: Love Stories and Ecstatic Cahoots: Fifty Short Stories, along with Childhood and Other Neighborhoods, The Coast of Chicago, and I Sailed With Magellan; and two volumes of poetry: Brass Knuckles and Streets in Their Own Ink. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including a 1998 Lannan Award, a Whiting Writers Award, and a MacArthur Foundation Award, among many others. Considered a master of the short story, Dybek writes in a lyric prose style that combines a strong sense of place with evocative, emotionally charged and often fabulist imagery.

Dybek’s voice is famously gritty and tender, and the stories here are set primarily in the Little Village and Pilsen neighborhoods of Chicago where he grew up: in the Catholic churches and butcher shops and factories and dead-end streets, all portrayed in vivid and dreamlike detail. The stories in The Coast of Chicago do not strictly adhere to traditional realism, though there is that too: the blown-out streets, as in the epic “Blight,” and the lovely spiraling memories in a cup of coffee in the classic “Pet Milk.”

But it’s the leaps of imagination that make The Coast of Chicago so believable. A classic of this collection, “Hot Ice,” is a fabulist tale that tells of a local legend, a girl “frozen in a block of ice” by her father after she tragically drowns and is rumored to be hidden in a local ice house. After years of hearing the rumors, three Chicago youths go looking for her.

The saint, a virgin, was uncorrupted. She had been frozen in a block of ice many years ago.

Her father had found her half-naked body floating facedown among water lilies, her blond hair fanning at the marshy edge of the overgrown duck pond people still referred to as the Douglas Park Lagoon.

That’s how Eddie Kapusta had heard it.

One of the best definitions of fabulism I’ve read comes from Debra Spark. In her essay, “Curious Attractions: Magical Realism’s Fate in the States,” Spark spells out what makes the premise both magical and real. The term magical realism, it turns out, is credited to Latin American critic Angel Flores, first mentioned in a paper presented at the Modern Language Association conference in 1955. As Flores found, and Spark explains, “magical realist stories often had one element that could not be explained away by logic or psychology and once the reader accepted that as a ‘fait accompli, the rest [of the story] follows with logical precision.” It turns out that fait accompli is the thing I’ve loved about the style, that the magical simply happens, and the narrative follows in accordance, and as Spark says, “adheres to logic and natural law.”

“Hot Ice” meets Flores’ criteria for magic realism—the virgin in a block of ice cannot be “explained away,” and like so many of Dybek’s stories, moves seamlessly from gritty realism to the magic of invention. Dybek shows us “…the Greek butcher shop on Halstead with its pyramid of lamb skulls,” and the stained glass window of an angel at St. Procopius, “its colors like jewels and coals,” and the fait accompli in the story’s central image, the saint trapped in a block of ice.

The Coast of Chicago also contains contemporary masterpieces like “Chopin in Winter,” and “Death of a Right Fielder,” along with a series of interconnecting vignettes and Dybek’s singular use of language and image.

Also, there is the classic “Pet Milk” (first published in The New Yorker in 1984), as perfect as a story gets. It centers on the narrator’s memory of the canned milk swirling in the grandmother’s instant coffee, an image that spawns other images, her ancient yellowed radio “usually tuned to the polka station, though sometimes she’d miss it by half a notch and get the Greek station instead.” One image leads to another, and in a structure, the writer Maud Casey brilliantly described as a spiral, like the swirling milk of the title, the images wind gradually inward, circling memory and an evening with a girl that ends in an erotic encounter in between El cars, and an ecstatic, time-traveling moment. The story expands the bounds of literary fiction, in its mix of time, memory, image, and voice, and that level of story-telling genius is what makes Dybek one of contemporary fiction’s best.

Read an interview with Stuart Dybek here.

—Lauren Alwan

Other Titles by Stuart Dybek

Northernmost, by Peter Geye

Many works of literary fiction have a very strong sense of place. Just think of all the works you can list where the places they are set in – New York, Chicago, New Orleans, the Pacific Northwest, the Texas Panhandle – are integral to the story itself. But other places seem to exist more as tropes, reinforced by humorous stereotypes. Places like Minnesota.

When you think of Minnesota, what comes to mind? Snow. Cold. Taciturn Scandinavians. Hot dish and jello salads. Yah, sure, you betchas. And you’d be right, but only by scratching the surface. If you want to know what it is to accept the cold, to embrace the snow, to glimpse the true mien of those taciturn Scandinavians, you could do no better than to read the works of Peter Geye.

Author of four novels all set in Minnesota, his most recent – Northenmost – follows two generations of the Eide family (whose other generations are also at the center of his books The Lighthouse Road and Wintering). We first meet Greta, a modern day writer living in Minneapolis with her husband and two children, whose extended family of Norwegian descent has lived in northern Minnesota for generations. Greta is struggling with the growing knowledge that her marriage has failed, and trying to reconcile the life in which she grew up with where she now finds herself.

But the novel also centers around Greta’s great, great, great grandfather, Odd Einer Eide who, in 1897, returned to his village of Hammerfest, Norway after being lost in the Arctic during a sealing hunt. Presumed dead, his reappearance captures the notice of a heralded newsagent, who wishes to publish his story of survival. As he recounts his ordeal, as well as tries to rebuild his relationship with his wife, we see a man who is willing to give up on his god and his life, but never on the faith he has in his family.

The juxtaposition of the woman who is surrounded with practical comforts yet feels emotionally numb with the impoverished man who is challenged by frigid circumstances yet confronts a spiritual awareness is masterful. When Greta, on a whim, takes a side trip to her ancestral home of Hammerfest while on her way to Oslo to confront her husband, she finds herself contemplating an unexpected awakening, a “thawing” of her frozen self. Odd Einer, also, finds himself on an unexpected path upon his return to Hammerfest as he struggles to express his ordeal as well a reforge a complicated bond with his beloved wife. Through it all, the intimately bitter landscape of the Arctic, the harsh Norwegian coast and the sweeping austerity of northern Minnesota lends itself to a deeply personal assessment of self that is brutally honest, hard to witness, yet ultimately compelling and uplifting.

Nothernmost, my friends, is the Minnesota I would love for you to experience. It is also a marvelous, engaging, and singular read, regardless of the environs you find yourself.

— Sharon Browning, Living in Minnesota

Other Titles by Peter Geye

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our other LitStack Recs for our recommendations on books you should read, as well as these reviews by Lauren Alwan, and these reviews by Sharon Browning.

As a Bookshop, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and Lumas affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

You can find and buy the books we recommend at the LitStack Bookshop on our list of LitStack Recs.