Passage to Ararat, by Michael J. Arlen

“It’s a dangerous business,” writes Clark Blaise in this book’s introduction, “going into the underworld of history and ethnicity to discover one’s father, yet it seems one peculiar duty in our time of identity politics.” The observation is an apt one in which to begin Michael J. Arlen’s elegiac memoir, Passage to Ararat, winner of the National Book Award in 1975. The author undertook the aforestated peculiar duty against his better judgment, and uncertain of his feelings about the family’s shrouded and all but unknown Armenian ancestry.

“It’s a dangerous business,” writes Clark Blaise in this book’s introduction, “going into the underworld of history and ethnicity to discover one’s father, yet it seems one peculiar duty in our time of identity politics.” The observation is an apt one in which to begin Michael J. Arlen’s elegiac memoir, Passage to Ararat, winner of the National Book Award in 1975. The author undertook the aforestated peculiar duty against his better judgment, and uncertain of his feelings about the family’s shrouded and all but unknown Armenian ancestry.

Arlen, who in his long career has written numerous books and was television critic for the New Yorker, makes a journey to the source of his father’s heritage to confront his patrimony, and the silence of an Armenian past—a past of exile, of atrocities and mass murder committed against the Armenian people, 1.5 million, between 1915 and 1922.

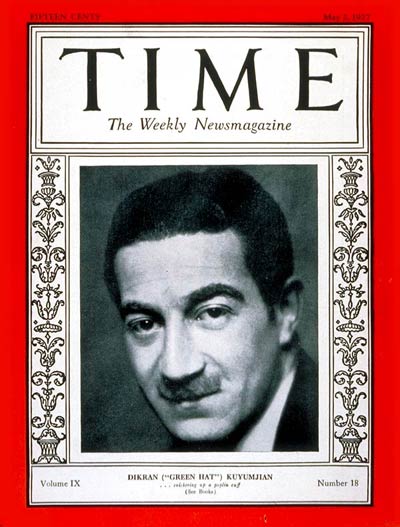

Arlen’s story is both memoir of that search and a detailed history of the Armenian people. Micheal J. Arlen was born in 1930 into a privileged life of villas and French boarding schools and upper crust life in Manhattan. His mother was the Countess Atalanta Mercati of Greece, and his father, the celebrated author of the 1920s, Michael Arlen, born Dikran Kouyoumdjian in Bulgaria. The elder Arlen is portrayed here not as the memoir’s subject (that takes place in the younger Arlen’s separate memoir, Exiles), but as its inciting incident. The father’s silence turns out to be the motive for the son to uncover its source, seeking the historical facts that brought about that silence.

The elder Arlen was a short story writer, novelist, playwright, essayist, and scriptwriter who became both rich and famous from a novel The Green Hat, as well as numerous collections of short stories (including These Charming People, reviewed here) all set in 1920s London. Famously well-heeled, a society figure who in his day was as famous as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway, the elder Arlen was, despite his wealth and fame, a perennial outsider. He reinvented his identity as a young man, choosing to distance himself from his Armenian past, a point the son mines in Passage—the family legacy of the genocide inflicted on the Armenian people who as Christians were forced to become refugees or slaughtered wholesale in villages across what was then Asia Minor (now Turkey).

Michael Arlen, the author’s father, on the cover of TIME, 1927.The account tracks the family history like mystery it is—the author must piece together both written history, oral accounts, and lived experience. We learn of his pilgrimage to California, to visit his father’s contemporary William Saroyan in the San Joaquin Valley. In one of the book’s best scenes, Saroyan leads him through an Armenian cemetery in a spring rain. “Saroyan was wearing a kind of old newspaperman’s hat—a hat from The Time of Your Life, maybe. Now he began to run at a trot through the graveyard. ‘Over there is Levon,’ he called. ‘I think one of Lucy’s sisters is over there!’ The grass was soft and slippery underfoot.”

Early in the book, Arlen and his wife, the writer Alice Arlen, take an extended trip to Erevan, the center of Armenia where snow-covered Mt. Ararat, the spiritual and geographic heart of the country and its culture, serves as a kind of fountainhead. Arlen prepares for the trip by reading every available history of the Armenian people, from the time of the Crusades onward. And throughout the trip, he keeps reading, holed up in his hotel between excursions led by their guide Sarkis to local sites, museums, churches, and villages. The character of Sarkis proves a kind of foil to Arlen’s lack of knowledge about how Armenians feel about pretty much everything—and with his seemingly one-sided view proves frustrating to the American author: “Armenians have no use for wars.” “We Armenians are peaceful people.” “We’re not European. We’re Indo-European.”

The discoveries Arlen makes, in his exploration of the country, his long conversations with its countrymen, and his extensive reading, bring a knowledge of the father through the atrocities that brought about the collective suffering. The discovery enables him to see his father more clearly. “I had seen how his face, with its coolness and authority, its supposed impassivity, concealed within it the silent, helpless fury of that man in the blue velvet hat. But it had taken me this long to understand where the fury had been directed: at himself, Dikran Kouyoumijian…how he must have hated growing up an Armenian in England…being himself marked, or feeling marked, by the collective guilt and self-hatred proceeding from a race that had been hated unto death.”

In the end, Arlen finds that collective history, one that helps explain the family history—within his father, and in other fathers too. Ironically, after leaving Armenia, he makes a stop in Istanbul where he discovers another Dikran Kouyoumdjian, an Armenian with a name identical to his father’s. That meeting, which is both awkward and endearing, is poignant. Arlen doesn’t learn about his father specifically, but the encounter offers a new experience of intimacy all the same.

On that night in California, when Arlen says goodbye to Saroyan, the old man embraces him, and says, “Fathers and sons are always different. But they are also the same. Maybe you will find out about that, too.”

—Lauren Alwan