Cabaret has always been a story about desperate people hoping to create a place for themselves.

In this LitStack Review

Based on the Novel, Goodbye to Berlin

Cabaret’s also always been a LGBTQ+ story as well and remains relevant to today, a cautionary tale about what happens when one goes along to get along. That theme is a through-line beginning in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood, published in 1939, to a Broadway play based on the novel, then a Broadway musical, then a Hollywood musical and, finally, to a wonderful and intensely emotional production of Cabaret that I attended last month at the Great Barrington Stage in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The ending of that production was the most moved I’ve ever been in the theater.

The Origins of Cabaret Are Complicated

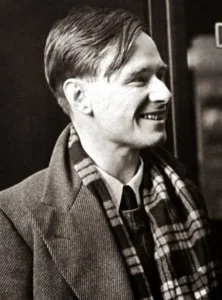

The original Isherwood stories in Goodbye to Berlin, were his semi-autobiographical tales of residence in Berlin in the 1930s as the Nazis were coming to power. Isherwood portrays the residents of his apartment building, his not-quite-a-romance with Sally Bowles, his landlady, Frau Schneider, and numerous friends and acquaintances. They’re episodic and slice-of-life tales and include a romance-coded friendship between two of his male friends. Isherwood, who was openly gay later in his life, is not explicit about the gay content in Goodbye to Berlin but it’s absolutely clear to anyone reading today. In the beginning of Isherwood’s stories, the Nazis are barely mentioned.

By the end, they’re taking over, and the narrator witnesses some stunning acts of violence. Some Germans fight, some are the aggressor, but more simply stand by.

Sally Bowles occupies only a slim slice of Isherwood’s novel but makes an indelible impression as a callow young woman who is only interested in others for what they can do for her. She’s only nineteen in the stories. Her actions, while not admirable, may be excusable in a young person who doesn’t yet know themself.

But Bowles is the character who caught the attention of other creative souls, first in the 1951 play I Am a Camera written by John Van Druten, and then, in 1966, at the center of the musical Cabaret with music by John Kander, lyrics by Fred Ebb, and book by Joe Masteroff. Isherwood remarks on this relinquishing of his ownership of the story in his introduction to Goodbye to Berlin:

“Watching my past be thus reinterpreted, revised, and transformed by all these talented people upon the stage, I said to myself: ‘I am no longer an individual. I am a collaboration. I am in the public domain.’”

Cabaret: From 1966 to Now

Cabaret the stage musical is an amalgam of the Isherwood stories and the vision of the play’s creators. They integrate some of the characters and lift many of the lines. But the musical is centered on the denizens of the Kit Kat Club, who are explicitly not-straight, while in the novel, the club is in the background. In Cabaret, Cliff the writer arrives in Berlin and is immediately pulled into the scene around the Kit Kat Club that includes Sally, the dancers, and members of the audience.

Cliff is smitten with Sally but it’s not entirely clear why—perhaps he sees her as the substitute for the family he wants but can never have. (The play is clear that Cliff is denying his attraction to men.) The story swirls around the need to create a world where LGBTQA+ people can be themselves. But it’s an insular world. Instead of being alarmed, they block out the rise of the Nazis with the assumption it’s just ‘politics’ and that the Nazis will come and then go and they’ll survive any changes.

Indeed, the chief Nazi of the play is the man who first takes Cliff to the Kit Kat Club. In the production at Great Barrington, most of the characters were explicitly LGBTQA+.

At the end of Cabaret, only a few characters refuse to go along with the Nazis. The rest either willfully join them or fear the cost of opposing them is too high. The play includes a subplot of a sweet romance between the landlady, Frau Schneider, and a Jewish fruit merchant. There’s an enchanting number about his gift of a pineapple. But she finally turns her back on him in the song “What Would You Do?” Frau Schneider bemoans she must choose between love or survival, but eventually breaks off her engagement. Carrie Buckley was stunning in this number in the Great Barrington production, filled with all the pathos as what she perceives as no choice.

(In the novel, Frau Schneider lacks a romance and commits anti-Semitic acts.) At the end of the play, it’s clear everyone at the Kit Kat Club is afraid and life has been irrevocably changed by the Nazis.

The novel and the musical have one thing in common: the characters at the center of the story are in denial about the true depth of the Nazis’ hatred, save for Cliff, who eventually leaves Berlin without convincing most people of the danger of the Nazis.

This is Cliff’s experience of the Berliners’ reaction to a Nazi attack in Goodbye to Berlin: “The crowd dispersed slowly, arguing. Very few of them sided openly with the Nazi: several supported the Jews; but the majority confined themselves to shaking their heads dubiously and murmuring: “Allerhand!” (The last is German for ‘all sorts.’)

The Theme of Cabaret Today

The original novel and musical are clearly a warning about viewing the rise of fascism as just politics or a phase that just passes. “What Would You Do?” is a direct challenge to the audience to consider their potential role in either opposing or appeasing the Nazis or other organizations like them.

When Isherwood published the stories in 1939, he was clearly disturbed at the trend of the general population going along with the cruelty of the Nazis. It was less a cry to action, however, than relating his own experiences and his own concerns about what was next. When the musical was first performed in 1966, the full horror of the Nazis has been revealed to the world. The audience is filled with the knowledge of the coming dread but “What Would You Do?” is merely an academic question.

But in 2023, as I sat stunned at the ending of a tremendous production of Cabaret, that question has renewed relevance, especially with the organized attacks on the LGBTQA+ community and even on speech that dares to mention them. (Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay.’) Our current political situation puts us in the position of Isherwood’s original narrator, witnessing a rising problem. But unlike Isherwood’s Cliff, we’re not leaving Berlin to go back home. We’re the Berliners.

The cast in the performance I attended was absolutely aware of the contemporary background to their performance. There was a stunning number that ended with the Emcee stripping to a G-string decorated with a swastika. That number was to appease the new customers at the Club, to treat the change in political parties simply as a matter of swapping allegiances. But even so, it becomes clear that characters fear something horrible is coming. This production ended abruptly, with half the cast having accepted what’s become inevitable and the remainder fearing what’s next.

What would you do, indeed?

~Corrina Lawson

Other Books by Christopher Isherwood

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and check out other LitStack Reviews to find out what to read, and also check out other articles by Corrina Lawson.