This week, we recommend The Custom of the Country, by Edith Wharton, and Shakespeare in Kabul.

In This LitStack Rec:

The Custom of the Country, by Edith Wharton

I knew from the start that things would go badly for Ralph Marvell. He’s a writer who spends more time thinking about writing than actually doing it:

‘You ought to write’; they had one and all said it to him from the first; and he fancied he might have begun sooner if he had not been urged on by their watchful fondness.

Enter Undine Spragg, a small town girl from the ironically titled town of Apex, North Carolina, he mistakes her for his muse. But in fact, Undine is the anti-muse, an arriviste in early 20th century Manhattan, a party girl whose loves to “go round” with the see-and-be-seen set. Besides her social network, money is of course Undine’s primary interest—large amounts of it.

Edith Wharton published The Custom of the Country in 1913, and set it in New York’s Gilded Age, before the cataclysm of World War I. Ralph Marvell is the last of a breed, a gentle soul whose musty peerage and links with the most aristocratic of the upmarket crowd attract the attentions of Undine.

And though opposites attract, as the old chestnut goes, it can be hell living together, as Ralph soon finds out. He’d rather retire to the family library and ponder his poetry than squire Undine, the golden-haired, glittering It-girl to another midnight supper or night at the opera. Even after Undine abandons him for the deep-pocketed Peter Van Degen, I had hopes for Ralph, since by then he’d finally begun the book he’d always dreamed of writing.

Yet just when it seemed they might agree to separate lives, Undine divorces Ralph and wins custody of their only son, Paul, via marriage to a hidebound French aristocrat—but even then, Ralph never finishes the novel. Undine’s lesson in greed may come to a bad end, but Ralph’s bad end is a lesson in what not to look for in your muse.

Wharton’s classic tale of ambition and class striving clearly hits a contemporary chord. It was recently the inspiration for a Vogue fashion shoot, photographed by Annie Leibovitz on location at The Mount, Edith Wharton’s Lenox, Massachusetts, estate. In 2020, Sofia Coppola announced she will develop Wharton’s novel as a series for Apple TV. “Undine Spragg is my favorite literary anti-heroine and I’m excited to bring her to the screen for the first time.”

Read Penguin’s Reader’s Guide for The Custom of the Country.

—Lauren Alwan

Other Books by Edith Wharton

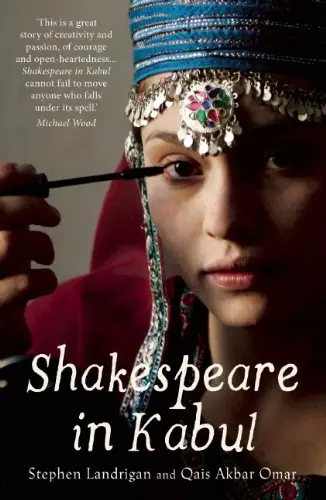

Shakespeare in Kabul,

by Qais Akbar Omar and Stephen Landrigan

In March 2005, a chance meeting in Kabul between a French actress and a British playwright allowed for something amazing to happen: a first ever theater production of Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost in Afghanistan by Afghan actors and actresses (with men and women appearing on stage together for the first time in almost 35 years) in a native Afghan tongue open for all audiences. Shakespeare In Kabul, written in tandem by Stephen Landrigan (the chance playwright) and Qais Akbar Omar (lead translator/assistant to the director) chronicles the project from conception to the development of the script, the hiring of the actors, the rehearsals and finally, the performances.

Kabul in 2005 was awash in optimism. The strict fundamentalism of the Taliban had been exiled, and Kabul’s population had begun to relax after years of debilitating warfare. Rebuilding could be seen everywhere in the city, and foreigners – and foreign aid – were also making a strong comeback. In this hopeful atmosphere, Dutch philanthropist Robert Kluijver and his Foundation for Culture and Civil Society was looking for a follow-up to a wildly successful music festival in Mazar, and had contacted actress Corinne Jabar to hold workshops for Kabul’s emerging actors.

But Corinne had a bigger, loftier dream. Drawing on the Afghani love of poetry and to foster a sense of universal appreciation of the spoken word, she envisioned an Afghani theatrical production of one of the world’s greatest poets: William Shakespeare.

Chronicling the many struggles and triumphs of this project, Shakespeare in Kabul is a faithful recounting of how daunting a task Corinne and her fellow organizers had undertaken. Even the struggle to come up with a script that would be accessible to Afghan audiences as well as acceptable to religious sensibilities while keeping the beauty of the rhyme, meter and meaning of Shakespeare was epic.

But add into that a very different culture in the basics of how life operates, a different sensibility in humor and social interactions, the huge challenge of having to translate all communication between director and actors, while operating under a very tight budget and with limited resources, and you start to understand just how incredible it is that the performances saw the light of day.

But Shakepeare in Kabul tells a much deeper story. It relates the hopes and fears of a proud people who were emerging from an iron fist of oppression, bolstered by centuries of cherished history and strong ties to their land and culture. Wounded but not defeated, cautious and yet extraordinarily open, the individuals who populate this book give the reader – especially Westerners – an eye- opening perspective on modern Afghanistan, allowing us to glimpse its people’s daily struggles and expectations.

Perhaps the most telling of these wrenching stories were in the audition process for the play. While Afghans have a very long and proud tradition of poetry and the spoken word, their theatrical traditions are far less prevalent, and finding qualified actors and actresses who could handle the Shakespearean text proved to be a daunting task. Part of the process included asking the potential cast members to improvise on a theme of their choosing; many would-be applicants had a hard time even understanding the concept of “improvisation”. But others not only took the assignment to heart, they opened their hearts and laid them bare for the sake of telling a story as actors and Afghans:

“Life in those days was nothing but a chain of struggles, of fear and of death. But you, Omar jan, made my black days as bright as the sun. And one day as I was in the kitchen cooking for you, your favorite dessert, ferni, a blind rocket from Gulbuddin landed on your room while you were still asleep, and you still had not told me your dreams of the night.

The noise of the rocket was so loud that I could not hear anything. I was dizzy, and everything smelled of gunpowder, and dust was everywhere as if it had conquered the whole earth. I staggered to your room, and saw a big mound of rubble, all in a pile, the roof beams, the mud bricks. But there was no trace of you.”

These were the everyday experiences of the Afghani people during wartime, which had lasted so long and left no one untouched. It is humbling how reflections of their lives could be pulled up so immediately and spoken of so personally. It’s easy for many of us to push acknowledgement of what this land has gone through aside, with conflicts happening half a world away and buried in newsprint and rhetoric. But when you put a face on the conflicts, when a struggle is paired with a name and a personality, it’s harder to ignore, harder to discount.

Yet ultimately, art triumphs. After many setbacks and compromises, through the heat and the dust and the language barriers, despite the bruised egos and numerous roadblocks that crop up, the show does go on – and goes on splendidly.

Yes, at times the prose is a little clumsy in Shakespeare in Kabul, and occasionally the transitions are somewhat abrupt or confusing to Western sensibilities. The conflicts that arise can seem strange to those who are not from the Middle-East and sometimes the background for these conflicts is only tangentially explored.

There are not enough pictures of the production and no reference index for those who may want to learn more of the project and its aftermath. But there is also great beauty in the writing, not just of the play and its cast, not just in the language of the story, but of the land and the backdrop of Kabul itself. Of the teeming energy in and around the city. Of the depth of history and the deep conviction of the people, and the amazing tenacity of their spirit.

If you are a lover of theater, of Shakespeare, of human triumph; if you like learning about new places and people, if you enjoy having a global situation witnessed through native eyes, or if you simply like a good story told in an honest and engaging way, pick up a copy of Shakespeare in Kabul. After all, it was the Bard himself who said, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” The stage set in Shakespeare in Kabul is indeed worth the watching, and these players will remain with you for a long time.

—Sharon Browning

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our other LitStack Recs for our recommendations on books you should read, as well as these reviews by Lauren Alwan, and these reviews by Sharon Browning.

As a Bookshop, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Audiobooks.com, Amazon, and Envato affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

You can find and buy the books we recommend at our Bookshop by clicking our LitStack Recs banner.