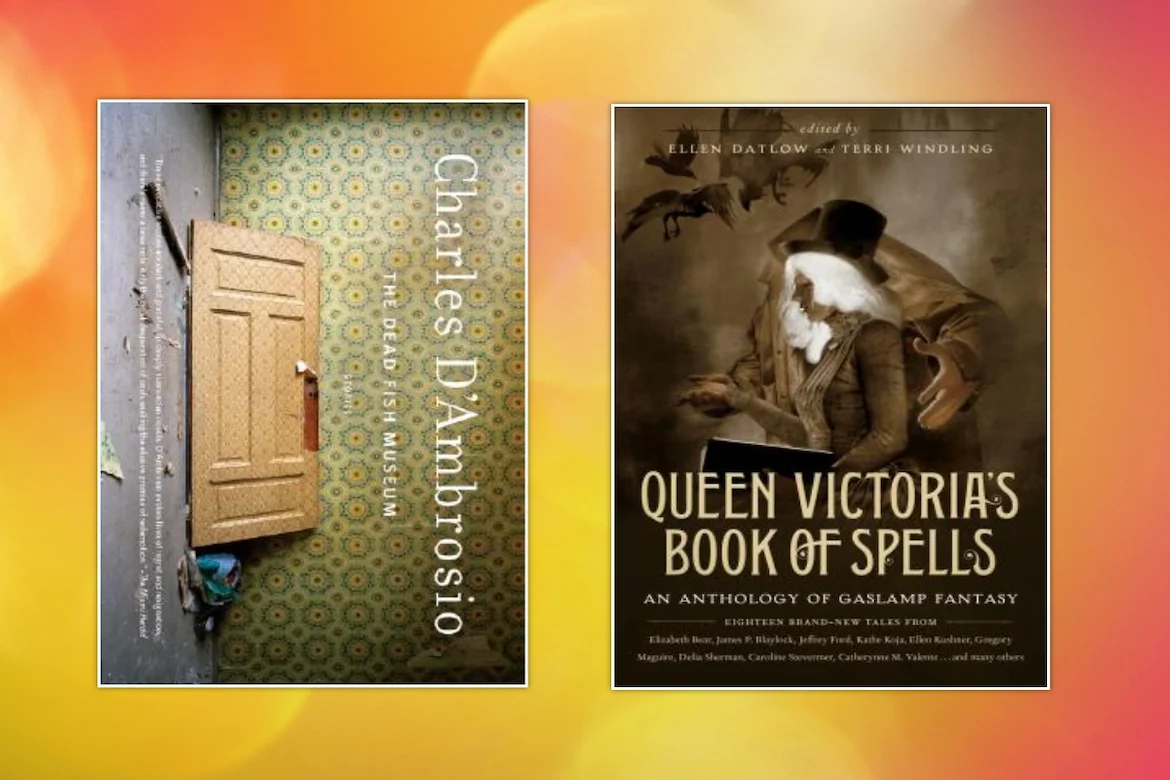

Stories, stories, stories! This week we are recommending two books of stories. First, we recommend Charles D’Ambrosio’s The Dead Fish Museum, and second we recommend Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells. Enjoy!

You can find and buy the books we recommend at the LitStack Bookshop on our list of LitStack Recs.

In This LitStack Rec:

The Dead Fish Museum, by Charles D’Ambrosio

A classic read is Charles D’Ambrosio’s 2006 story collection The Dead Fish Museum, set in the Pacific Northwest landscape, home to the majestic Shasta Cascade mountain range, conifer forests, and crisp air, a place that in these stories informs character. Of the author, and this book, Michael Chabon has said, “Charles D’Ambrosio works a rich, deep, dangerous seam in the brokenhearted rock of American Fiction. His characters live lives that burn as dark and radiant as the prose style that conjures them,” and the Los Angeles Times Book Review places D’Ambrosio, at “the top tier of contemporary practitioners of the short story.”

That praise is well deserved. These eight stories are rich and at the same time, austere. In “The Bone Game,” first published in the New Yorker, Kype, the grandson of a local magnate has lost his way in Portland’s confusion of one-way streets, circling Pioneer Square with a hitchhiker named D’Angeloan, and an urn of his dead grandfather’s ashes on the seat:

“Kype finally found the street he wanted and steered the car north through Pioneer Square. An Indian sat on the curb with his head in his hands, tying back two slick wings of crow-black hair with a faded blue bandanna. A pair of broken-heeled cowboy boots lay in the gutter while he aired his bare feet. D’Angelo rolled down his window, waved a gun in the air, took a bead, and dry-fired. The hammer struck three times against empty chambers, but in his mind D’Angelo had dropped the Indian, right there on the sidewalk. He raised the barrel to his lips and blew away an imaginary wisp of smoke.”

The tone that recurs in this collection, dark certainly, but also wry in the way of the audacious characters whose actions often feel last-ditch. Kype and D’Angelo finally head out to the coast, and on the way pick up a young Makah woman, Nell Ides, and the three make for Port Angeles. D’Angelo turns on the charm, telling Nell about Kype’s rich grandfather and their plans:

“You may have heard of him. Kype, his name was Kype. Just like this guy. Anyway, me and my friend Kype here, we’re drinking the old man’s bourbon, and we got his old gun, and we’re going to catch the biggest, wildest fish in the ocean with his old fishing pole.”

“Putting the fun back in funeral,” Nell said.

The book is thematically rich with the complex view of outsiders, of the Pacific Northwest’s Native culture and lore, of history, geography, industry, tragedy. In “Drummond and Son,” the younger Drummond runs a typewriter shop he’s inherited, in itself anachronistic, while his own son, Pete, is developmentally disabled. Drummond brings him to shop each now that now his wife has left, and there’s a tone throughout of loss, and of isolation—that comes with Pete’s difference, with the end of a marriage, with fixing beautiful old things that are becoming increasingly obsolete:

“Drummond wore a blue smock and leaned under a bright fluorescent lamp like a jeweller or a dentist, dipping a Q-Tip in solvent and dabbing inked dust off the type heads of an Olivetti Lettera 32. The machine belonged to a writer, a young man, about Pete’s age, who worked next door, at La Bas Books, and was struggling to finish his first novel. The machine was a mess.”

There is “Up North,” a haunting story of a hunting trip, that male trope of nature, power, and bonding, that D’Ambrosio uses to peel back the layers of pain around trust and intimacy in a marriage.

In “Screenwriter,” the titular writer confined to a psych ward for attempted suicide, befriends a ballerina he met on the ward. She’s getting better, he’s not: “Departures on the psych ward were a big deal. People always swore they’d come back and visit but they never did. By the time you were a ward veteran like myself a little bit of your hope left with them and never fully returned.” It’s a kind of obsession with her, but also with her healing, which isn’t going as well for him. “Aren’t you exhausted?” she asks him, suggesting that the heart and soul can tire of the weight of grief, and perhaps heal. Or not.

D’Ambrosio is the author of The Point and Other Stories, and Orphans, a collection of essays. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Zoetrope All-Story, and A Public Space.

Read my appreciation of Charles D’Ambrosio’s essay collection, Orphans, at The Rumpus.

—Lauren Alwan

Other Titles by Charles D’Ambrosio

Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells

Edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling

Take 19 established and talented writers. Give them the chance to craft stories full of fantasy, magic, alternate history and/or visceral horror. Mix in a Victorian-era mindset and a nod to lingering folklore, with perhaps a puff of punkish steam, and hand them off to two of perhaps the most accomplished editors of the day, and you have Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells.

This focused yet far ranging anthology – each tale is set in the 19th century – has something for all fantasy tastes, with every one of the 18 short stories proving to be quite engaging. Not all of the stories have Queen Victoria as a character and not all of them involve spells, but all of them look at life in the Victorian age in a unique and quite imaginative way.

Take my three favorites, very different, but very evocative. In the initial offering, “Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells” by Delia Sherman, we find a modern Yankee researcher delving deeply into the British Royal Archives, granted grudging access to an ancient folio suspected of harboring secret insights into one of England’s most revered figures. In this iteration of our world, magic and sorcery are common and many bluebloods had been well schooled in the magical arts.

But only recently had the full extent of the Queen’s abilities been explored, and what the young researcher uncovers is a view of Victoria unlike any other, explaining with a supernatural bent some of the mysteries of her reign. Yet beyond the historical import, the unraveling of Victoria’s spells allows us to witness the hopes and fears of not just one, but two strong, intelligent, yet ultimately lonely women.

Limited magical education, my sweet aunt Sally. Clearly, there was more to Our Dear Queen than even the most revisionist historians imagined. Reggie is going to be delighted. I just wish I didn’t feel quite so much like a trained pig, hunting for truffles.

“La Reine d’Enfer” by Kathe Koja is a tour de force of language used to encapsulate a world familiar yet lost in the past. Set in the seedier side of Victorian England, this Dickensian tale follows a young London street urchin whose fair looks and penchant for recitation mask a dark and powerful secret. To young Pearlie, all of his dirty world is a stage on which he performs, and the most rapturous of words merely a means to an end. At times unflinchingly brutal, “La Reine d’Enfer” spins a story of seizing opportunity, where the players evoke no sympathy and yet make your heart ache at the same time.

Davey had his own way of talking, and he taught me to talk it as well, that is, the kind of elocution that gets a fellow somewheres in this world. The way the gentlemen like for you to talk, to pretend that what you do with them is a lark for both of you, a jolly wolly roly-poly while they’re dosing you with the Remedy and sodding themselves off.

The speech patterns, phrases and unapologetic expressions of life in the alleys and back rooms are strong and coherent throughout the entire work; even when you don’t exactly know what is going on, the dark pictures drawn are still clear and immersive – and chilling. Sometimes it’s truly hard to tell who is the victim in this story, and who is the one preying on others, even in the name of survival.

Also chilling is the tale “Phosphorus” by Veronica Schanoes, which completely circumvents the glamour of the Victorian era by focusing on the very real exploitation and suffering of the working class. Set at the time of the “matchgirl strike” of 1888, where workers at the Bryant & May Factory (makers of phosphorus matches known as “lucifers”) walked out in protest of working conditions and unfair labor practices, “Phosphorus” chronicles the life of one young woman who has contracted “phossy jaw”, a condition caused by coming into contact with the toxic phosphorus element which rots the bones in the jaw and leads to eventual organ failure.

It begins with a toothache. And those are not uncommon, not where you live, not when you live. Not uncommon at all. But you know what it means, and you know what comes next, not matter how hard you try to put it out of your mind. For now, the important thing is to keep it from the foreman. And for a while, you can. You can swallow the clawing pain in your mouth just as you swallow the blood from your tender gums, along with your bread during the lunch break. If you have bread, that day. A mist of droplets floats through the room, making the air hazy, hard to see through. They settle on your bread.

Your teeth hurt, but you can keep that from the foreman. You can eat your bit of bread and keep that secret.

But then your face begins to swell.

Combining historical events with wrenching human drama, and folding in Irish folklore and superstition, this story is permeated with a sense of helplessness, hopelessness and sacrifice. These voices from our past that author Schanoes has resurrected are truly haunting, due, yes, to the spectral elements, but also as a remembrance of how far we have come and to what we owe the cavalier way in which we live our modern lives.

And these are just three of the 18 stories in this entertaining anthology.

Some of the other tales are equally imaginative, ranging from a decidedly mercenary treatment of fairies in the burgeoning era of the Industrial Revolution (“The Fairy Enterprise” by Jeffrey Ford) to what happens to Scrooge and the others after A Christmas Carol ends (“A Few Twigs He Left Behind” by Gregory Maguire); from a frenetic fantasy of manners born from an imaginative letter game (“The Vital Importance of the Superficial” by Ellen Kushner and Caroline Stevermer) to the sweet story of a truly literary creation (“Estella Saves the Village” by Theodora Goss), Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells holds jewels for everyone – including some that may be unexpected, but will be treasured all the more for that wonderful discovery.

—Sharon Browning

Other Anthologies from Ellen Datlow

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our other LitStack Recs for our recommendations on books you should read, as well as these reviews by Lauren Alwan, and these reviews by Sharon Browning.

As a Bookshop, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Audiobooks.com, Amazon, and Envato affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

You can find and buy the books we recommend at our Bookshop by clicking our LitStack Recs banner.