This LitStack review takes a look back at the 2019 release of A Woman Is No Man reviewed here by Lauren Alwan.

In This LitStack Rec:

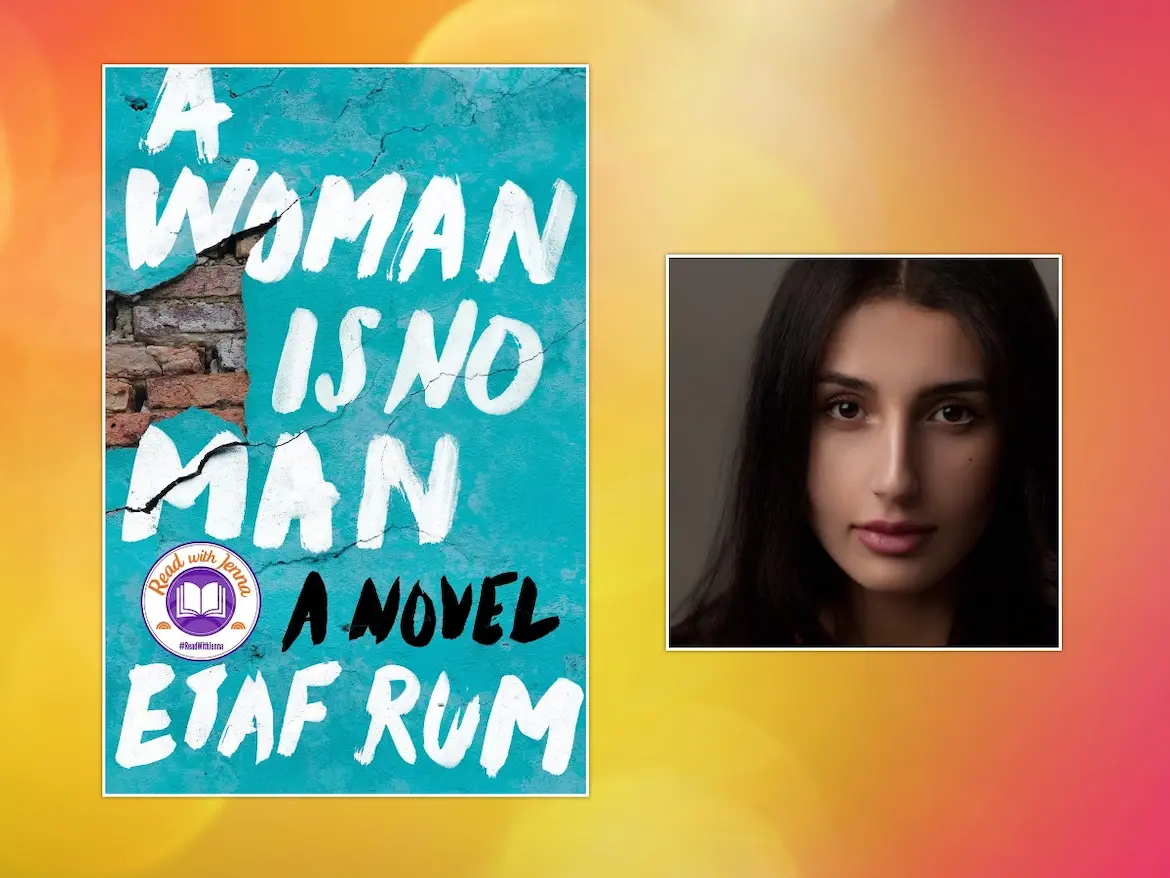

A Woman is No Man, by Etaf Rum (Harper, 2019)

“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” So runs the epigraph by Maya Angelou that introduces Etaf Rum’s bestselling novel A Woman is No Man. Of all the conditions that can keep a story hidden, shame and the silence of oppression are among the most painful to bear, and the women in Rum’s novel bear both.

A Woman Is No Man is Rum’s first novel, and was named among the most anticipated releases of 2019 by Yahoo.com, Marie Claire, and The Millions. Called “a richly detailed and emotionally charged debut” by Kirkus Reviews, and named A Goodreads Choice Awards Finalist, as well as A New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, USA Today Best Book of the Week and many more, the novel is an intergenerational portrait that looks unflinchingly at domestic violence, family loyalty, honor, and the cultural bias toward women, all against a backdrop of late 90s-early aughts New York.

“Where I come from,” says Isra Hadid, “we’ve been taught to silence ourselves, that our silence will save us.” She arrives in the US from Palestine, married by arrangement at 17 to a striving immigrant shop owner, Adam Ra’ad, and is by nature shy and deferential. She copes with the cultural shock of Bay Ridge by doing as she’s told and asking no questions, all while bearing the untold story inside her. The couple lives with Adam’s parents, the embittered patriarch, Khaled, who still bears the emotional scars of exile by Israeli soldiers from his home in Ramla, and his wife, the imperious matriarch Fareeda, along with their four as yet-unmarried children, including the youngest and only girl, the independent-minded Sarah.

The narrative braids two timelines, moving between Isra’s arrival in the US, and eighteen years later, when her eldest daughter, Deya, comes of age—and is being introduced to suitors for marriage, all of whom she rejects. The tension of the two storylines lends itself to the mystery at the heart of the novel. Early on, when time leaps forward, we learn that for the past decade, Deya and her three sisters have been raised by their grandparents: Isra and Adam, as the girls have been told, died in a car accident, but the adults will say little else. With Isra’s fate known from the start, her death becomes the mystery that Deya seeks to solve, and does, by uncovering a history of family secrets. These include Adam’s physical abuse of Isra that leads to a violent turn of fate, one that Isra, who lacks advocates or protectors, cannot escape.

“That was the real reason abuse was so common, Isra thought for the first time. Not only because there was no government protection, but because women were raised to believe they were worthless, shameful creatures who deserved to get beaten, who were made to depend on the men who beat them.”

The family’s cultural expectation that girls be chaste, devout, deferential, and inconspicuous runs counter to the life the second- and third-generation girls experience outside the home. Isra spends her days mostly confined to the large house in Bay Ridge, cooking, cleaning, and waiting on Fareeda while Khaled and Adam run the deli. Fareeda, like Isra, married and bore children at a young age, and harbors secrets of her own, venting her anger and sense of injustice by imposing harsh cultural demands on Isra, Sarah, and later, Isra’s daughters. In the Ra’ad family, wives and daughters are expected to follow strict Muslim traditions. American-born or not, they must marry by arrangement upon graduation from high school and bear children—especially sons—while cultivating a home life for their husbands and families. As the wife of the eldest son, Isra is expected to produce boys, but instead gives birth to four girls. With each birth, Isra’s standing in the family lessens, and an already difficult relationship with the distant Adam is further strained.

Strict as the household is, there are contradictions. Fareeda concedes that being “too Arab” will hurt the girls’ chances for acceptance by American-born Arab suitors: “…they weren’t a devout Muslim family, not really. Once, Deya had contemplated wearing the hijab permanently, not just for her school uniform, but Fareeda had forbidden it, saying, ‘No one will marry you with that thing on your head!’” Both Adam and Khaled are chronically inebriated, a source of shame that the family never acknowledges due to the cultural prohibition against alcohol. Deya comes to understand the contradictions are rooted in social conformity: “most of the rules Fareeda held highest weren’t based on religion at all, only Arab propriety.”

Deya unravels the mystery of her parents’ death with the help of Sarah, estranged from her parents after refusing to marry and choosing college instead, though they must meet in secret. This bond between the second-generation Sarah and third-generation Deya reflects a solidarity that Rum’s characters seem to long for: the support of an elder woman whether mother, sister, aunt, or grandmother, who can use their standing to advocate for the powerless younger girl. Sadly, it’s an advocacy that not all the characters receive.

We learn that Isra tries to combat her voicelessness and lack of agency through reading—a passion conducted at the risk of punishment by Fareeda who believes that Western ideas will do nothing but corrupt a girl’s mind. The escape into literature is an impulse Isra shares with Sarah, and one that becomes a lifeline for Deya as well. For Isra, the books Sarah brings provide a new perspective on the world. “For so many years she had believed that if a woman was good enough, obedient enough, she might be worthy of a man’s love. But now, reading her books, she was beginning to find a different kind of love. A love that came from inside her, one she felt when she was all alone.” In this novel, the cultural inheritance passed between the three generations of women centers not on custom or tradition, but a love of books.

The theme of literature as a haven reflects the author’s own experience. The daughter of Palestinian immigrants, Etaf Rum was born and raised in Brooklyn. The eldest of nine children, she entered an arranged marriage at 19 and soon had two children. Rum was however able to attend college, majoring in philosophy and English and eventually earning a master’s in American and British literature, and currently teaches undergraduate courses in North Carolina, where she lives with her two children.

Rum’s portrayal of the Arab community has raised questions about the depiction of stereotypes of Arab men as oppressive and violent and Arab women as submissive. “I wanted to write an authentic story about the lives and struggles of many Arab-American women,” the author has said. And while she acknowledges “there is always a danger in having a single story represent an entire culture or community,” Rum believes that breaking the silence around this topic is necessary. “In some Arab-American families, domestic violence is the norm. But it’s important to recognize that it’s rooted in culture. Our mosques favor equality between men and women, and they’re completely opposed to domestic abuse. Still, in the home, and in the wider community, it is tolerated.”

The novel challenges this cultural tolerance for domestic abuse. Her characters are steeped in a generational culture clash—the first generation aims to preserve ideals and traditions of the life they knew in Palestine, determined to provide their children with the advantages of life in the US yet wary of American culture and what they perceive as its negative influence on the morality of girls and women. As the younger generation grows up in the more tolerant and open culture, the earlier generation holds on to its secrets, and silences, and sadly, this include the degradation of girls and women.

Rum’s prose style is direct and plainspoken, with an engaging immediacy, as here, when Sarah reflects on possible sources of contentment, “Revolutions don’t come from a place of happiness. If anything, I think it’s sadness, or discontent at least, that’s at the root of everything beautiful.” It’s a lovely conceit, and given the weight of these characters’ lives, there were instances when I longed for more of the language to rise, as these lines do, to the level of their circumstances.

And yet, A Woman is No Man is a book that breaks a silence, and whether in the Arab community or any other, the silence of domestic abuse is entrenched and lethal. I admire the risk Rum takes in holding up a subject that intersects with stereotypes of Arab men, women, and families. In a culture that is traditionally private and uses silence not only with the outside world but with family as well, these stories of Arab immigrants in America must be known. Domestic violence is not exclusive to Arab culture, but Rum exposes a dark subject, one that intersects with centuries of patriarchal culture and male dominance that speaks across culture. As Fareeda reflects on the notion of female independence, she recalls her mother’s remark, “A man leaves the house a man and comes back a man. No one can take that away from him. But a woman was a fragile thing.”

—Lauren Alwan

Titles by Etaf Rum

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and look at our other LitStack Recs for our recommendations on books you should read, as well as these reviews by Lauren Alwan, and these reviews by Sharon Browning.

As a Bookshop, BAM, Barnes & Noble, Audiobooks.com, Amazon, and Envato affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.