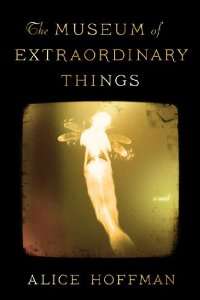

The Museum of Extraordinary Things

Alice Hoffman

Scribner

First Edition: February 18, 2014

ISBN 978-1-4516-9356-0

Part fairy tale, part morality play, part historical fiction, Alice Hoffman’s 31st novel, The Museum of Extraordinary Things, pays homage to New York City in 1911. While much of the action takes place prior to 1911, that is the pivotal year in the story and Ms. Hoffman’s brilliant narrative makes New York come alive, whether it be the crowded streets of Coney Island, the Jewish tenements on Ludlow Street, the textile factories on the East side of Washington Square, the posh neighborhoods along Park Avenue or the woods that still remain north of Upper Manhattan.

Here we have communities of displaced Orthodox Jews who have fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe, marveling at the magnificence of the Eldridge Street Synagogue but choosing to worship in their own nondescript building in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge. There are characters such as Abraham Hochman, the “Seer of Rivington Street”, who could find missing persons (among other services) and was fabled as being a wizard, but who actually employed a cadre of street-wise boys who knew how to watch and listen without attracting attention. There was the grumpy old hermit, Jacob Van der Beck, whose family owned a large track of land beyond Riverside Park where the Hudson still was shielded by wilderness; he lived there in a rundown shack, fearful of the encroachment of the city and attempting to stave off its advance with a shotgun in the crook of one arm and a bottle of rye whiskey in the other. But men such as these are just side players in our tale.

The Museum of Extraordinary Things is the story of Coralie, daughter of Professor Sardie, world class magician turned scientist who left France and sleight-of-hand behind him to move to Brooklyn and establish the Museum as homage to what he ordained were scientific wonders, rare and unusual, but what others would label as freaks of nature and unnatural. Coralie herself had a birth defect that left her with webbed fingers, which she kept hidden under black gloves even on the hottest of summer days. Yet after her 10th birthday (before which she had been forbidden to enter the Museum, due to her tender age and childish sensibilities), she herself became an attraction billed as “The Human Mermaid”, as her father had for years subjected her to a regimen of rigorous swimming in the Hudson and learning to hold her breath underwater for long periods of time, as well as regularly being submerged in cold water, all in the name of bolstering her constitution.

But that is Coralie of the past. Coralie of 1911 is one whose days of museum attraction are waning; the Human Mermaid is no longer new and exciting. Also, greater and more spectacular exhibits are to be had in the nearby Dreamland, a Coney Island amusement park that offers not only freak shows but exciting animal attractions, thrill rides and other peculiar amusements. Set back by this larger and more lucrative competitor, Coralie’s father is hard pressed to find fresher and more fantastical exhibits to keep his own dream afloat, an effort which weighs heavily on the entire household.

The Museum of Extraordinary Things is also the story of Ezekiel – Eddie- Cohen, penniless refugee from the Ukraine with his Orthodox Jewish tailor father who earned a scant living in one of the many brutal clothing factories on the East Side. The Eddie from 1911 is estranged from his father and has turned his back on the faith of his ancestors, believing more in the power of gin than of God. But he had always been a boy who had been able to see the shadows, and he, somewhat by accident, had become the apprentice and then beneficiary of Moses Levy, a master photographer at a time when taking pictures was rarely considered an art form.

Alice Hoffman takes the story of these two young yet lonely hearts – one whose life has been based on lies and manipulation, the other whose life has been ravaged by misunderstanding and hardship – and allows it to slowly weave itself into a single story of love and the search for truth and then in turn, strength. In beautiful language, she brings us into the world of two lonely people, and lets us see a spirit still burning in each.

The evenings were still damp and chilly even though spring had arrived, and the dusk fell in sheets that were mottled and fish colored. Coralie went to the shoreline where she had first learned to swim. The water’s pull was difficult to resist; she could feel it in her blood, stinging like salt. It was here the whole world opened to her, as it always had, in a grid of sand and sea. Shea had come to believe that if her father had wanted a docile daughter, he should never have allowed her access to the ocean. It was here she found a strength that often surprised her. Perhaps she was not a spineless creature, but a wonder after all.

The book also weaves elements of real events and real places into the story, with two tragic fires as major threads that set into motion actions that reverberate throughout the rest of the narrative: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, where 126 young women and 23 men toiling as garment workers were killed when fire broke out in a run-down building where entire floors had their doors locked and their windows nailed shut to keep workers from taking breaks, and the Dreamland fire, which completely leveled the famed amusement park and wreaked panic and flames along blocks worth of Coney Island, causing millions of dollars of damage and putting over a quarter of a million people out of work. Ms. Hoffman’s depiction of these two horrific fires is simply harrowing, and demonstrates how very real people were affected by what we today so casually dismiss as history.

The Museum of Extraordinary Things does move at a slower pace than some readers may be used to; it is, after all, written with 1911 sensibilities. But while the action may not move at the fast clip of works in a more contemporary setting, the thoughts and emotions run very deep, tantalizingly so. Along with the beautiful language and well researched world in which the reader is enmeshed, the story itself will satisfy in any way it is taken: as a realistic fantasy, an arcane-ly modern morality play, or as enlightened historical fiction. For many, it will satisfy as all three, which is a testament to the talents of the author, indeed.