Jane Austen’s 1813 novel “Pride and Prejudice” is a classic of literature with fans across eras and generations and perhaps one of the most famous first lines in the genre:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

In This LitStack Rec:

A Classic Version Of The Stranger-Comes-To-Town

Mr. Bennet, gentleman of a modest estate, Longbourn, in Hertfordshire, must somehow marry off his five daughters. In what has now become a classic version of the stranger-comes-to-town, the novel’s marriage plot launches with the arrival of Charles Bingley, a gentleman of means, from London. Through Charles, the Bennets are introduced to Mr. Darcy, who’s both the novel’s hero and antagonist. He’s also the romantic foil of the Bennet’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth. Through a series of classic Austenian misunderstandings, events bring Mr. Bingley and Jane—the second eldest daughter—together, then apart, and Elizabeth and Darcy spar in a classic romantic trope of crossed signals.

Pride and Prejudice For Both Small And Big Screens

All ends well, of course, as marriage plots do. And given the smart dialog, the beautifully opposed characters, and romantic settings, Pride and Prejudice (originally titled First Impressions) has seen numerous film and television adaptations and spinoffs. In 1940, MGM’s Pride and Prejudice starred Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson, with Aldous Huxley co-writing the screenplay. Of the small screen versions, the BBC’s 1995 series, with Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle is still considered one of the best.

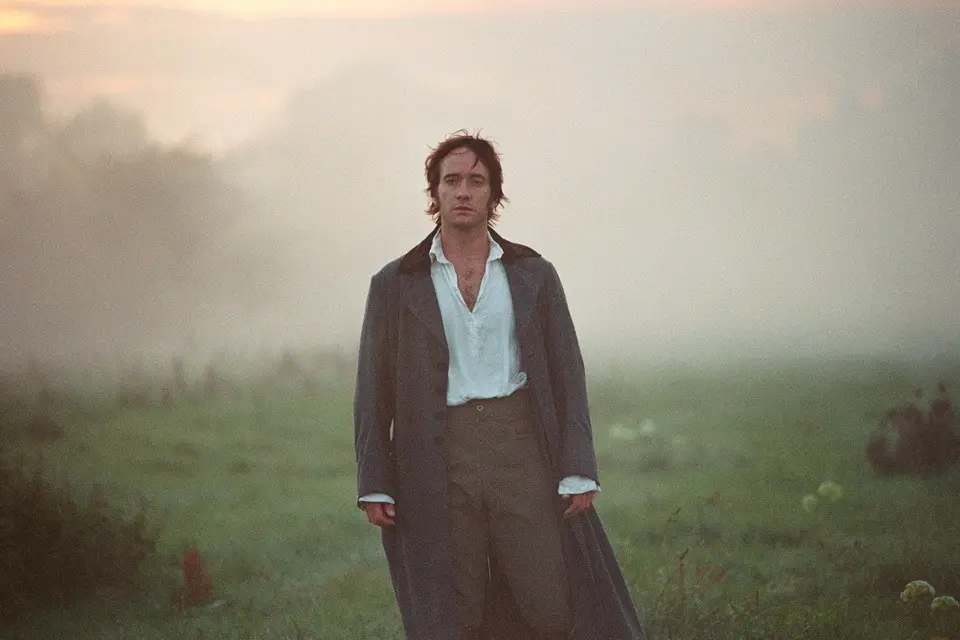

My favorite, directed by Joe Wright for Working Title, and released in 2005, is superbly cast: with Donald Sutherland, Brenda Blethyn, Rosamund Pike, Claudie Blakely, among others, and Dame Judi Dench as the haughty Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Luminous casting aside, the film has become legendary for its penultimate scene of Darcy and Elizabeth meeting at dawn in a misty field, and as Fitzwilliam Darcy, Matthew Macfadyen’s impossibly romantic progress across the meadow to a transfixed Kiera Knightly.

Wright signed on to direct the film not having read Austen’s book or seen any of its filmed versions, yet his adaptation lies closest to the spirit of young people, their romantic impulsivity and their challenge of the period’s class structure. As a companion text, Austen’s book colors the energy of that world in a way film cannot—bringing language to the romance, the constraints, and the beautiful particulars that give Austen’s characters beating hearts.

Her words of course offer insight and deeper detail that enlarges the film, beyond the nuances of the actor’s performances in a film as good as Wright’s. We see too how the screenwriter, English novelist Deborah Moggach, makes the novel her own by playing with Austen’s novel structure (with some editorial additions by Emma Thompson) She shifts dialog between characters, combines or changes the order of scenes, and arranges events to produce a seamless, engaging story that holds to the original while tightening the action for a contemporary audience.

Fully-Drawn Characters, On The Page And Onscreen

Take the obsequious Mr. Collins, cousin of Mr. Bennet and sole male heir to Longbourn. In the film, played brilliantly by Tom Hollander, Austen’s vision for the character is unmistakable. He’s affected, obsessed with class hierarchy, and perpetually out of sync with those around him. Here’s Austen introducing him:

Mr Collins was not a sensible man. and the deficiency of nature had not been assisted by education or society, the greatest part of his life having been spent under the guidance of an illiterate and miserly father. And though he belonged to one of the universities, he had merely kept the necessary terms without forming at it any useful acquaintance.

Socially awkward, perhaps even slightly depressed—established in his deadpan dinner conversation (“What a superbly featured room and what excellent boiled potatoes”), in Mr. Collins we see Austen’s text confirming what we observe, but perhaps cannot articulate, in Hollander’s brilliant interpretation.

Or take George Wickham, Darcy’s one time friend, now an opportunistic lothario. Wickham’s entrance into the novel is nothing short of grand:

His appearance was greatly in his favor. He had all the best parts of beauty. A fine countenance, a good figure, and a very pleasing address.

As Wickham, Rupert Friend plays his character close to the vest, a subtler interpretation than Hollander’s, and perhaps by necessity, as it’s Wickham’s duplicitousness that drives the action. Friend’s portrayal of Wickham taps into that uncertainty—we’re duped along with Lizzie and the Bennets, while Darcy sees him with the clear eyes of experience.

Austen’s “Solid Burns”

Given the frictions that lace the plot, there’s plenty of what Book Riot calls solid burns, and reading them is perhaps even more satisfying than seeing them performed.

Here’s a great one, spoken by Mr. Bennet to Mr. Collins on his visit to Longbourn. It’s delivered in response to the cousin’s preening around his complementary abilities with young women—and most interestedly, it’s Lizzie who, in Wright’s film, gets to speak this choice remark:

It is happy for you that you possess the talent of flattering with delicacy. May I ask whether these pleasing attentions proceed from the impulse of the moment, or are the result of previous study?

Naturally, Darcy has plenty of burns as well. “Men of sense do not want silly wives,” and “My good opinion, once lost, is lost forever.” But Austen saves the best for Elizabeth, the novel’s center. Here she is rebutting Darcy’s first, ill-timed attempt at a marriage proposal after she’s learned that he’s behind the separation of Mr. Bingley and Jane:

“From the very beginning—from the first moment, I may almost say—of my acquaintance with you, your manners, impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish disdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form the groundwork of the disapprobation on which succeeding events have built so immovable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world on whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry.”

Kiera Knightly’s stunning delivery of that burn can be watched right here from this article.

Watch Wright’s film (again), read Pride and Prejudice (again), and get lost in Austen’s delicious tangle of a marriage plot.

Other Jane Austen Books

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and click over to other LitStack Recs and LitStack Articles from Lauren Alwan.

As a Bookshop, Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.