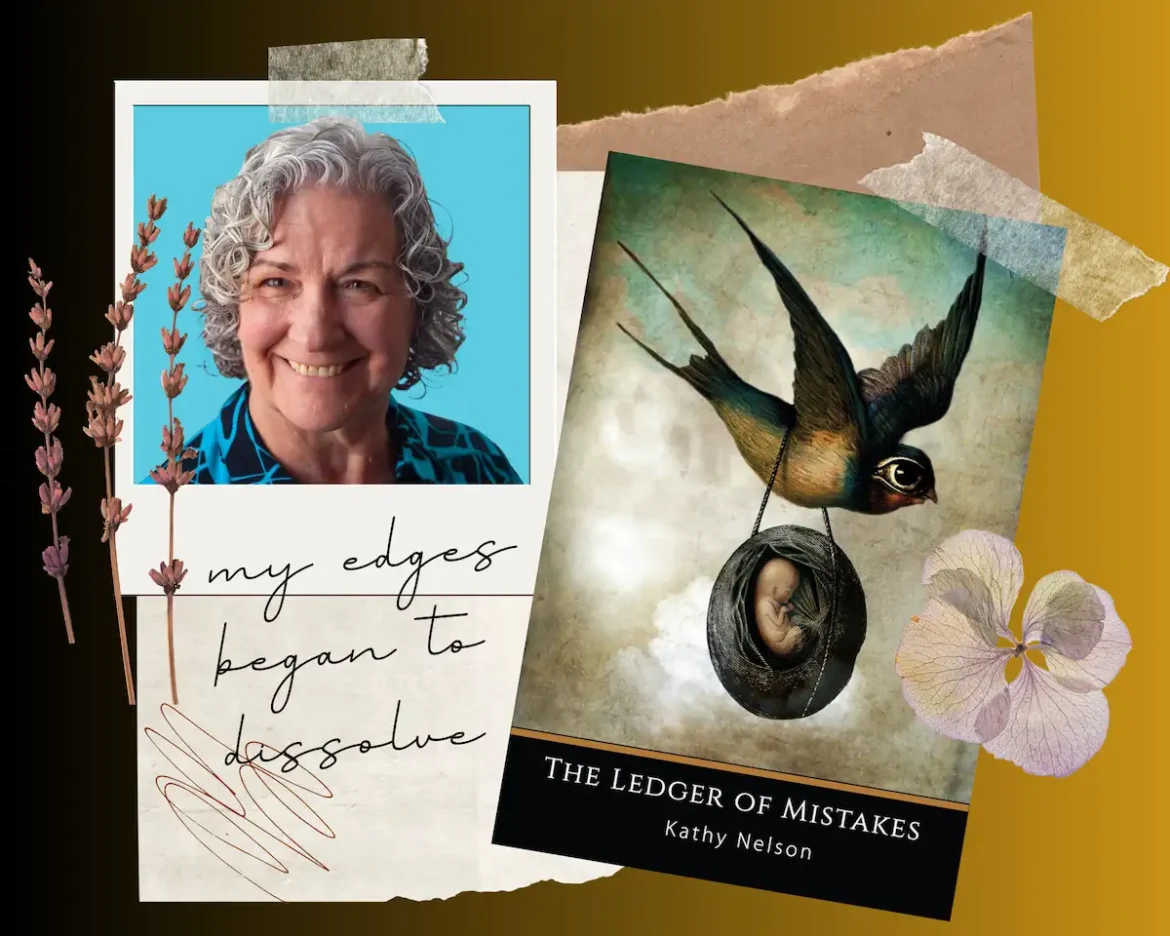

“…and my edges began to dissolve into the rising dark”

In This LitStack Review:

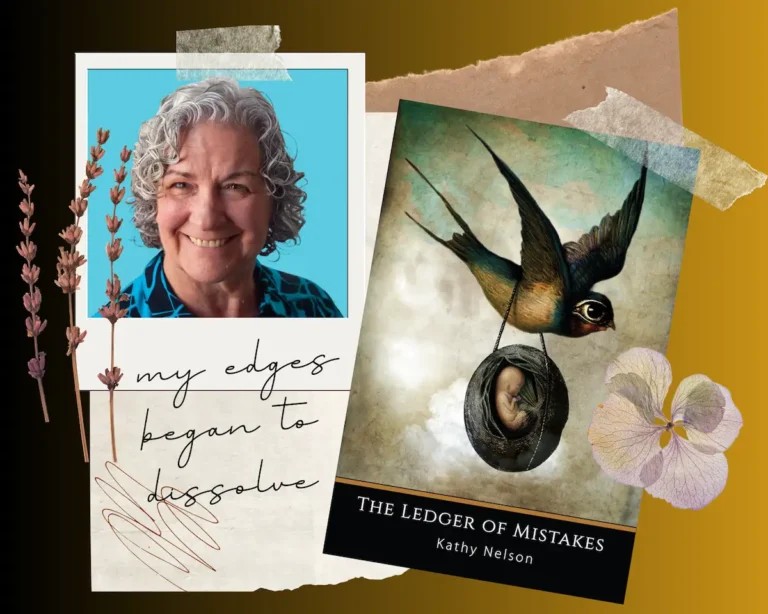

The Ledger of Mistakes

In Kathy Nelson’s The Ledger of Mistakes, the speaker grieves both the loss of her mother and the maternal love withheld in their relationship. The collection draws from—and feels much a living part of—the complicated process of attending to an elderly mother through her cognitive decline and death and, in that process, mourning their often difficult relationship. This is a point of connection for readers—both those who will consciously connect with this childhood dynamic and those who glimpse aspects of their unexplored experiences and feelings in this collection’s intricate and sensitive pages.

The considerable variety of poetic forms contributes to the thematic unity of the collection in reflecting the relentlessness of the poet’s processing of past and present, suffering and gratitude, compassion and apprehension. The collection’s formal diversity also creates a cumulative impression of a kind of peace with existential groundlessness, an embrace of flexibility. These organic qualities of the book are often dissonant with the book’s title, raising in the reader’s consciousness the dichotomy between two feelings of uncertainty: the patient attention to one’s own emerging thoughts and feelings as opposed to attempting to conform to the unpredictable behaviors of others.

Psychological Form

As the collection unfolds, the reader learns about the speaker’s relationship with her mother one impression at a time, mimicking the way internal reflection brings different memories and feelings back to consciousness. In this way, too, the book can serve as a model and companion for those undertaking such journeys.

Early on, “Eclipse” hints at hurtful aspects of the relationship. The speaker experiences a paradoxical gratitude for the opportunity, afforded by her mother’s cognitive diminishment, to express love for her without fear of reproach:

I loved enfolding her, as though after long absence,

and kissing the marble of her cheeks, forehead, each eyebrow,

over and over, while the barrier, long ago erected, crumbled.

“Eclipse” (7)

The deep sadness in these lines is that the speaker assesses the situation as safe for the innocent expressions of love for her mother, rather than feeling free to offer them in the trust of the maternal relationship. This self-protectiveness is embodied cleverly in the sentence structure itself, the kernel sentence “I loved” protected by the opening phrase in which the mother is perceived to be disarmed and also separated by “as though” from the child’s expressions of love for her mother. This isn’t disingenuousness or self-deception; it’s consciousness: The hurt and love are simultaneously present, even if logically contradictory. As readers, we develop trust for the speaker here: She is practical and reasonable while also loving and emotionally honest.

This highly conscious experience of love is an important context for poems that follow, such as “February”:

with scold, her lines end-stopped―inside, embroidery.

You’ll have to finish this. I’m unable.

It reads My Daughter, My Shining Star, the slate gray

thread stuttering around one pansy, languishing.

Her needle, trailing green, still stuck in the linen.

“February” (9)

The mother’s emotional blindsiding explains quite succinctly the speaker’s self-protectiveness in “Eclipse,” and the speaker distances emotionally from this painful scene and telling image by analyzing the speech as if it were a poem. Reading “February” after “Eclipse” recreates the experience of a memory recalled after a “barrier, long ago erected, crumbled,” the reopening of love for the mother triggering thoughts of why that barrier was there in the first place. The crafting of the poems and their sequencing in the collection work together to evoke various nuances within the processing and mourning of the relationship.

Improvisation and Resilience

“Boundary I” offers a glimpse of the speaker’s intuitive connection to the natural world in childhood, recalling when she “listened to the / moon and the frogs called and the katydids ticked and a / million molecules amassed into a nearness so large my skin / prickled and my edges began to dissolve into the rising dark” (8). Here the less painful memory is recalled by spending time with her granddaughter—but the speaker similarly follows her intuitions to the roots of psychological material.

This is shown to be an ongoing process in poems like “Mercy,” in which her mother’s dementia causes her confusion about their relationship:

Mama? I squandered the moment replaying

the words I’d always craved to hear, wondering

if she knew my name. Never mind

what you’re called when love speaks. I should

have kissed her cheek and blessed her back—

“Mercy” (25)

This poem deftly captures the interlocking complexities of thought and emotion that arise through this unintended and displaced version of the loving relationship the speaker craved. On the one hand, there is a sense that the speaker should take whatever apparent love comes from her mother’s person, lucid or otherwise. However, she has already seen through such hunger for affirmation in “Cake”: “Quickest of a thousand ways to suffer? Crave” (20). However, beyond these concerns, the poem imagines the speaker’s own maternal acceptance of her mother’s confused expression of love, an indirect expression of the speaker’s own inner strength and healing in the capacity to offer grace.

In “I Never Thought My Mother,” the speaker imaginatively encounters her mother as a “copperhead living under the porch” (26). Her fear, a “stitch at my sternum” caused by both snake and memory, connects the two. Interestingly, the prescient response to the snake plays into the old pattern of craving connection with the mother: “if I clear my mind of fear, we might / reconcile.” However, the speaker has a flexible reception of this cognitive dissonance – and even a constructive conception of further imaginative reincarnations: “She will return, one life to the next, / until I no longer need her.”

Through the self-reflective space of the poetic process, the speaker is able to improvise alternatives to the tendency to “crave” her mother’s affirmation. The poems themselves evidence the flexible strength that results in their fluidity and generosity of imaginative response.

Objects of Contemplation

“Easter, 1956” begins with the speaker recontextualizing a photograph: “I slide the photo from its frame again to see her hand / reaching, the way my hem drapes across her fingers” (15). The gentle connection opens to an association: “Once, in a dream, / I awoke from numb forgetting, remembered— / oh, the longing—a daughter I’d never known, / lost in the night.” The dream seems to provide an opening to a level of objectivity about her mothering relationships: “I have been my mother and I have been my daughter.” Moving the “frame” discloses in image the practice of the poem itself.

Indeed, the litany of balancing experiences associated with that claim cascade into the apparent duality in the final image: “I have shrunk from the cliff’s edge, / and I have marveled at the possibilities of flight” (16). The hesitancy to take flight recalls the gentler affect of her mother in this poem, “[n]ot so much restraining as inviting, coaxing me to defer escape from the camera frame” (15). This is one of the moments in the collection that seems to see all the way through the situation to its archetypal entanglement: The acknowledging of the mother’s moments and aspects of kindness pull on the speaker’s own love and the part of her that wishes to remain connected despite all else.

The final sentence is not, like those that prepare for it, oppositional. You can seek safe ground and “marvel” concurrently, as opposed to being “the swatter and the fly.” The final duality isn’t relational; it’s intrapsychic, what two different parts of the mind do in the same scene, perhaps in dialogue, or argument. The poem’s preparatory misdirection itself is an embodiment of the way two modes of mind can sometimes create unintended implications even while working cooperatively—and, at the same time, of how meditative insights tend to whisper themselves quietly—and how poets tend to tell them slant.

An inverse realization comes about in “At the Least Movement, the Whole Structure Collapses,” which opens describing the optical illusions in Albert Giacometti’s “The Palace at 4 A.M.” The speaker catches herself getting caught in the sculpture’s optical illusions, concluding in the surprising couplet: “A surrealist vision made of air. / My mother isn’t even there” (52-3). The ending links seeing what isn’t in the sculpture with recognition of an unconscious connection between the misperceived object and her deeper processing of complexities with her mother—crucially shocking readers out of our illusion of seeing these poems as objects separate from ourselves. We’ve been thinking through and empathizing with the speaker—it’s important to remember that those experiences are refracted through our own psychological contexts.

Being In Between

Beyond its insights into individual and interpersonal psychology, The Ledger of Mistakes participates in an ongoing meditation on death. “Rivals” begins with the mother’s displaced anger at the loss of her husband: “My mother never forgave me for being / the one who knelt beside my father, / my ear pressed, listening for his heart” (33). The placement of the poem’s two sections on opposite sides of the page physically embodies both the space between life and death and between willingness to face death’s reality and the mother’s wish to avoid it by assigning blame: “The list―the blanket, the ambulance— / all I could have done and did not―.” Here the meaning of “ledger” comes into focus.

This provides context for the collection’s opening: “Why remember the dead? Why finger / like prayer beads their hurts, hungers, / all I could never give them?” (3). We can see how these questions needed to be separated from one another. The second question, the collection has taught us, is not an inherent or logical follow up to the first. The speaker has shown us that we can remember the dead also to heal, to mourn authentically, to offer love, to imagine, to create.

“Cahokia” shows, in part, how these outcomes in the collection result from the speaker’s own acceptance of death. Its opening bypasses personal claims on the supernatural: “I don’t know how to be a vessel” (76). The poem explores inherited implications of vessels, but its grounding in the discovery of an older civilization indicates the speaker is uncomfortable with literalized, monological interpretations of the biblical meaning as well.

It leaves us, like the collection itself, with a dual valuing of the “reader” and the unknown, including its mortal implications: “I don’t know where in these woods / the copperheads are winding in their dens, / where / the turkeys are fattening on acorns, their necks ratcheting /down and up. If I knew how to tell you that, I would” (77). The informal tone conceives a reader like a conversation partner, poem and friend, perhaps, each esteemed for their help in relating to the other. The speaker repays this value in neither sidestepping mortality, nor pretending to have an answer.

The varied and nuanced pieces in this collection are invested with the many insights, acceptances, and revisions through which the speaker journeyed to find such a reader within. One essential process it models is this intertwined processing of the interpersonal and existential. Beyond our appreciation for its inventiveness and eloquence, it is a generous companion to anyone undertaking such travels.

~ Michael Collins

Books of Poetry by Kathy Nelson

Michael Collins, the Reviewer

Michael Collins’ poems and book reviews have received Pushcart Prize nominations and appeared in more than 70 journals and magazines. He is also the author of the chapbooks “How to Sing when People Cut off your Head” and “Leave it Floating in the Water” and “Harbor Mandala” and the full-length collections “Psalmandala” and “Appearances,” which was named one of the best indie poetry collections of 2017 by Kirkus Reviews. He teaches creative and expository writing at New York University and has taught at The Hudson Valley Writer’s Center, The Bowery Poetry Club, and several community outreach and children’s centers in Westchester. He is the Poet Laureate of Mamaroneck, NY. You can find and follow Michael Collins on Linkedin and his website notthatmichaelcollins.

Other LitStack Resources

If you enjoyed this LitStack poetry review, please stop by our Poetry page to find other reviews. Be sure and also check out other LitStack Reviews that provide in-depth critical examination of books you should read.

As a Bookshop affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.