In this LitStack Interview:

A Section on Graphic Novels

I recently browsed my local library and saw something that never would have existed when I was a kid over 40 years ago: a section for graphic novels. More, a section for newly released graphic novels covering genres from non-fiction to horror to biography and fantasy.

Graphic Storytelling Never More Robust

Graphic storytelling, in comics and graphic novels, has never been a more robust and popular story form, from the well-known DC and Marvel superhero stories to Dav Pilkey’s mega-bestselling books to the acclaimed work of Raina Telegemeier, to adult titles like Saga and Monstress.

Editor Joe Illidge has had a front seat to those changes for nearly three decades, beginning with Milestone Media, and continuing to his current work on MPLS Sound and Heavy Metal magazine. He was fascinated by the medium from a young age because of its’ unique blend of art and story. Like many of us who love the art form, he’s optimistic about its’ future. I interviewed him about why this type of storytelling is so unique, what makes for a great graphic novel, and his vision for the future of this kind of storytelling.

Our Interview:

LS: How did you get your start as an editor in the graphic novel world? What is it like to also write graphic novels? What are you currently editing?

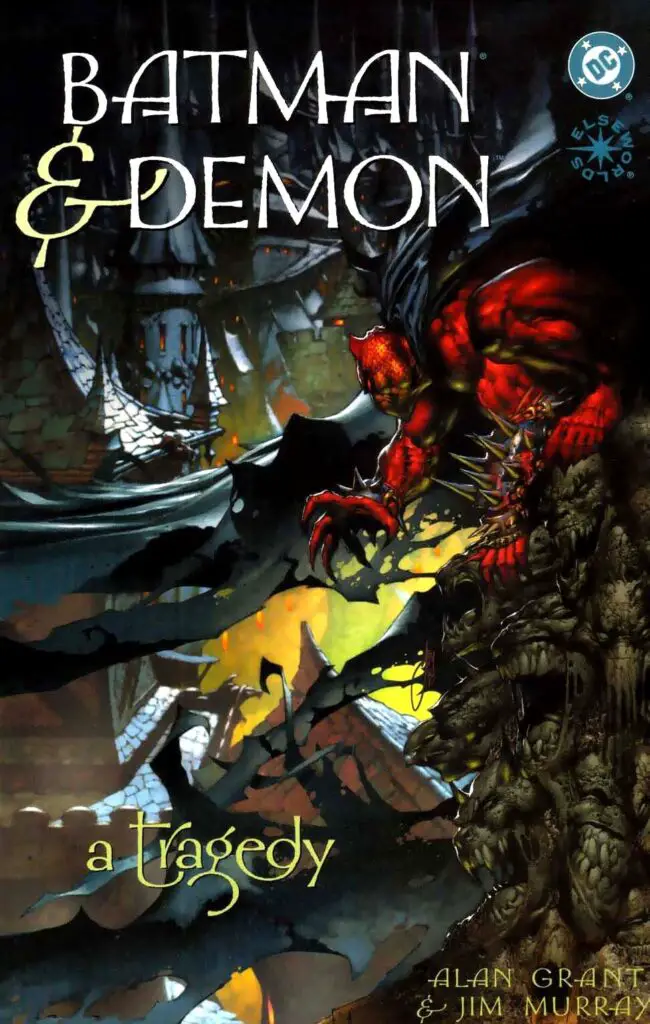

A few years after graduating from New York City’s School of Visual Arts, I started working at Milestone Media, the first publisher of multicultural hero fiction to have a co-publishing deal with an industry giant, DC Comics, now part of DC Entertainment. Working at Milestone led to my next job as an editor for the Batman department at DC, where I co-edited Batman/Demon: A Tragedy, a prestige format graphic novel painted by Jim Murray. I grew up on painted graphic novels like Elektra: Assassin by Frank Miller and Bill Sienkiewicz, so co-editing a painted book of such an iconic character really set me on the path to appreciate the format early in my career.

Writing graphic novels really helps me approach characters and drama with a sense that every scene is important and has to move the story forward because the reader gets a finite story in which the main characters have to go through a profound transformation. I recently worked on MPLS Sound, a historical fiction graphic novel set during the early rise of Prince in 1980s Minneapolis, which was published by Humanoids earlier this year. While it was fun to bring real-life musicians into the cast, I knew every scene had to push the main character of a Black woman forming a multicultural funk/soul band toward her destiny. I apply that rule of scenes always moving the story forward in both my editing and writing.

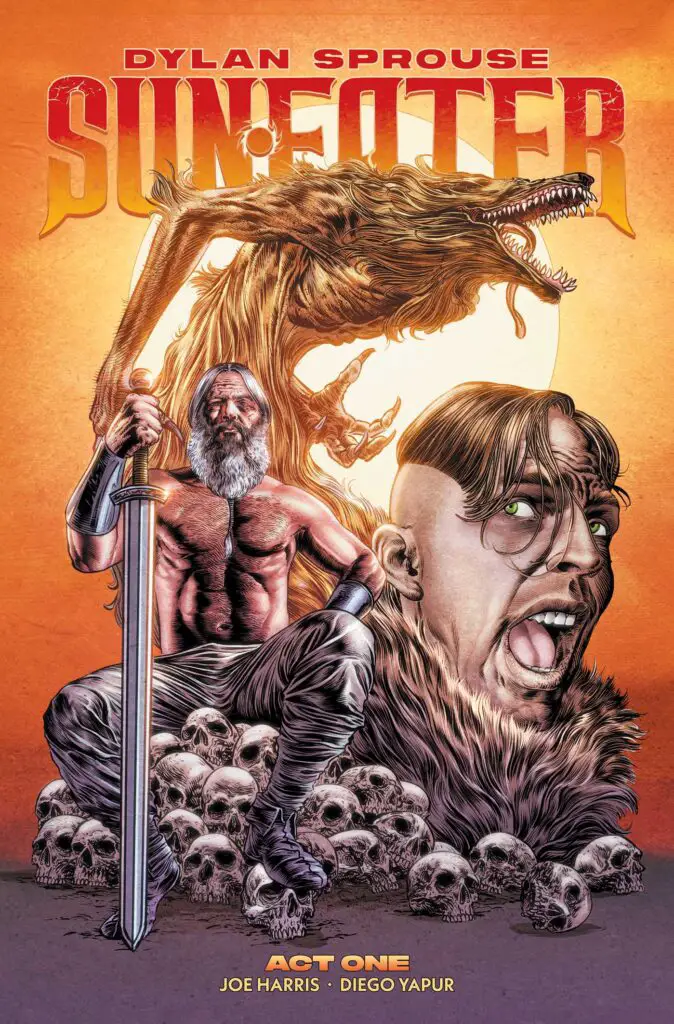

Right now, I’m editing graphic novels and the monthly Heavy Metal Magazine for my main client Heavy Metal as their Executive Editor, and I’m currently working on Sun Eater: Act Two, the second volume in our Viking horror story set in ninth-century Norway during the reign of King Harald. Actor and entrepreneur Dylan Sprouse crafted a tale that is both personal and fantastical, so it was great putting together the art team to bring that story to life with a style that is reminiscent of Howard Pyle’s King Arthur.

LS: What do you think is unique about graphic novels and why do you think we are so drawn to them?

The sequential art of graphic novels combines words and art in a unique way that makes it distinctive from all other narrative forms. Film and television are widely appreciated storytelling mediums, but graphic novels use time and visuals in ways that allow us to get inside a character’s private thoughts in ways that are fluid and unobtrusive. The art, dialogue, and inner thoughts are three layers of story, presented seamlessly.

I think people are drawn to graphic novels for a number of reasons. There are so many amazing and unique artists producing work right now that we’re immediately drawn in by the illustrated beauty of their books. We’re also seeing the full range of literary genres in graphic novels, so no matter what your tastes are, there’s a graphic novel out there for you. We’re experiencing a renaissance of the medium right now, and it’s a new frontier of discovery for many readers in the bookstores, which is pretty exciting.

Speaking for myself, I’ve been an avid reader since childhood and studied art in high school and college, so graphic novels brought both of my interests together in one art form that has its own unique strengths.

LS: What, in your experience, makes a good graphic novel? Can you tell it it will be good from the script or do you need art with it as well to know if it’ll be good?

A good graphic novel starts with the script. I’ll never forget when one of my art teachers from college, told the class that a good painting technique over a bad drawing won’t get you a good piece of art. It’s all about the foundation. The script is that foundation, and a really good one will inspire an artist to elevate the story to unexpected heights. Nowadays, half the time it seems the writer and artist of a graphic novel are the same person, so there’s a more personal synergy happening there. In other cases, it takes a good editorial eye and understanding of art to find the right visual artist to match up with the script.

Ultimately, it comes down to every member of the team being committed to telling the best story and having an editor act as their guide and ally through the journey.

LS: Are there any panel-by-panel constructions that you love? Conversely, ones that are overused or don’t usually work?

The beauty of the language is that visual form follows story function, so while I can love the nine-panel grid that Dave Gibbons utilized in Watchmen, David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp has a wide variety of page designs which make the story a joy to read and revisit. I don’t think any panel-by-panel construction is overused. For an editor, it’s best to have an open mind to what’s visually right for the story as opposed to applying a personal preference across different stories.

LS: What’s your favorite graphic novel panel of all time?

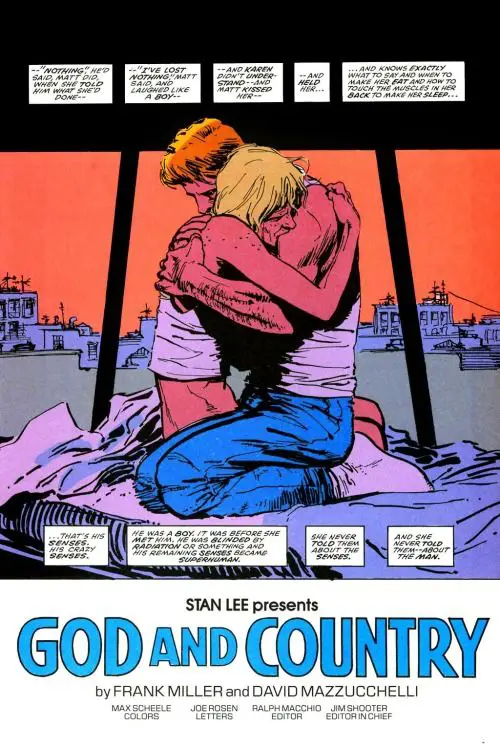

Frank Miller, creator of Sin City, David Mazzucchelli (you can see I’m a fan of his), Christie “Max” Scheele, and Joe Rosen produced a seminal crime-noir graphic novel of Marvel’s Daredevil character called Born Again. There’s a page with Matt Murdock, the fallen hero of the story, and his ex-girlfriend/resurfaced love of his life, Karen Page. The two are holding each other, on their knees. Karen is crying and biting into Matt’s shoulder. Matt is being silent and tender. There’s a red, nighttime sky in the background, and you can just feel the years they’ve lived through, that broke them, shamed them, and brought them back to one another. The words by Miller are beautiful, but even without them, it’s such an evocative page, a vulnerable moment. That page is my editorial north star, the white whale to my Ahab.

LS: As an editor, you’ve been in a unique position to see how things have evolved in the art form. What would you say have been the biggest changes? Is there anything from older styles that you miss? Are there any structures that you’d like to see used more?

That’s a tough one, because the language of graphic novels is still changing, never at rest. I think one of the biggest changes is that the form has gone back to the front, in a manner of speaking. Windsor McCay’s Little Nemo In Slumberland is over a hundred years old. Because the language and stories of graphic novels change with the zeitgeist, we’ve gone from the sublimely fantastic to the realistic and underground art that befitted the latter half of the Twentieth century, and we’ve made our way as a medium to a place where artists like Frank Quitely and Chris Ware brought us back to that McCay sense of wonder and design decades ago, and presently there is no single, dominant style to define the graphic novel. Graphic novels have arrived at a point of deserved recognition as an art form equal to others of considerable note and influence.

I miss the work of Barry Windsor Smith, but Fantagraphics released his graphic novel Monsters earlier this year, so I get to experience his level of craft once again. In terms of storytelling style, as opposed to structure, I really admire the way Will Eisner incorporated the environment in which a story takes place into the page design. I’d love to see more of that kind of surreal approach to storytelling.

LS: Where do you think graphic novels are going right now? Where do you see their audience?

Graphic novels are heading toward becoming a cradle-to-grave form of storytelling. I think that books like Dav Pilkey’s Dog Man can start kids on a road to middle grade, then young adult, then adult graphic novels, by giving them an understanding of the language of graphic novels just as easily as how kids now learn to use smartphones and iPads.

LS: What can we learn, perhaps, from the mistakes of the past going forward? What about the successes?

In the past, we underestimated the appeal of graphic novels to the layperson, someone who is not an aficionado of the language or format, but is looking for engaging, character-based, imaginative stories. Now, graphic novels are a gateway form of literature for teenagers, and adults are discovering graphic novels with as much depth and complexity as prose works.

In terms of the successes, I think back to an interview with Neil Gaiman that I read early in my career when he spoke about the virtues of the language of graphic novels, as opposed to graphic novels trying to emulate the virtues of other storytelling mediums. One of the reasons Saga by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples is so special is because it does not scream a desire to be something other than a story told within and because of the strengths of the graphic novel format. It aspires to be the best story it can be, told as a graphic novel. Yes, you could make an animated series from Saga, but that would be a by-product of a great story being adaptable in different storytelling mediums.

Before the pandemic, adults who watched HBO’s Watchmen series sought out the original graphic novel by Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins. It’s unlikely any of the creators made Watchmen to be adapted to film and tv, but it was such a distinctive piece of work that it challenged visionaries from other industries to adapt that world and stories of its inhabitants.

Once we stop viewing graphic novels for adults as niche, we open the doors to a wider range of possibilities for the publishing industry.

LS: What’s your dream graphic novel pitch, something you’d love to see be wished into existence?

From an editorial standpoint, a series of books by BIPOC storytellers which approach stories from a different prism than the established imprints are doing today. There is something that lies in between historical fiction and Afrofuturism.

From an author’s standpoint, I would tell you, but that’s between me and my literary agent for now. I have a few stories on the horizon, some of which will be announced soon!

~ Corrina Lawson

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and click over to other LitStack creative writing articles in our LitStack Toolkit, and also look at other articles by Corrina Lawson.

As an Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

2 comments

Wonderful interview, Corrina – thank you!

Excellent exploration of the past, present and future of graphic novels. Kudos, Mr. Illidge!

Comments are closed.