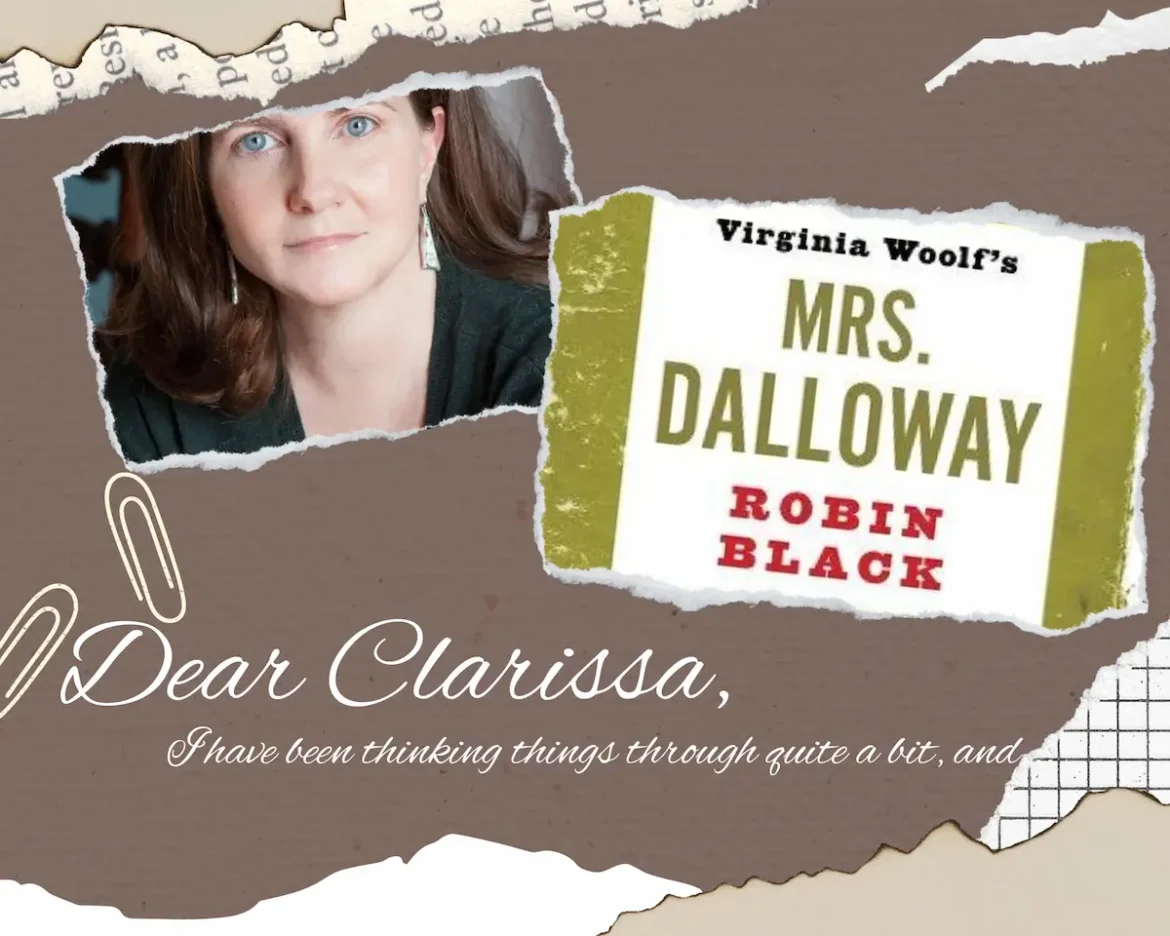

LitStack is proud to give you this review written by guest contributor, Nan Cuba, who offers attention and insights into Robin Black’s highly personal nonfiction title Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway.

In this LitStack Guest Review:

How It’s Done

In her Bookmarked contribution, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (Ig Publishing), Robin Black says her reflection on Woolf’s classic is written not from the perspective of a critic or scholar, but from a fiction reader and writer describing “what the experience of me, reading her book has been like.” In other words, it’s personal and told as though she’s sharing a confidence.

Robin Black’s story collection, If I loved you, I would tell you this, was a finalist for the Frank O’Connor International Story Prize, and named a Best Book of 2010 by numerous publications, including the Irish Times. Her novel, Life Drawing, was longlisted for the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, the Impac Dublin Literature Prize, and the Folio Prize. Her insights on craft and the writing life are collected in Crash Course: Essays From Where Writing And Life Collide. (Disclosure: She and I have been friends since we published with the same press.)

Identification with Woolf

…a woman raised in a household that valued intellectual achievement…

Robin suffers from attention deficit disorder, which made her school years challenging. At Sarah Lawrence College, when classmates praised Virginia Woolf, she read the letters, journals, and biography, but avoided the novels because they were “difficult.” She identified with Woolf, reinventing the author and conveniently overlooking the suicide. “[W]hat I needed her to be,” Robin says, “was this: a woman raised in a household that valued intellectual achievement above all else, who had a brilliant and difficult father, who suffered from mental illness, and yet, who somehow got the last laugh because the world recognized her as a genius.”

The point was that if Woolf could rise above her problems, Robin would surmount the limitations of her ADD and trauma of living with an alcoholic, depressed father, and someday also be seen as a genius. When she finally read Mrs. Dalloway at forty-two as an MFA graduate student, her idolization was replaced with gratitude for the novel’s assistance in her evolution as a writer, and respect for Woolf, especially her courage to create a character, Septimus Smith, who had the author’s same mental illness, something Robin could never imagine doing.

Doubling

Robin quotes from Woolf’s introduction to the novel’s 1928 Modern Library Edition in which she says Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Smith, a WWI veteran with PTSD, are fictional strangers functioning as doubles. Robin explains a list of the characters’ similarities and differences, but primarily, she says, they both have a “concern over life’s meaning in [death’s] shadow.” They struggle with “whether life is worth living.” Clarissa copes by decorating her home with flowers, hosting a party, and, she hopes, “mitigating the suffering of our fellow prisoners”; Robin calls this Clarissa’s religion. Septimus, without adequate mental healthcare, cannot cope and commits suicide. When Clarissa hears about his death, the narrator says, “She felt somehow very like him.”

Reading about that connection between the characters, one can’t help but recall Robin’s earlier statement when describing her years of struggling with ADD, agoraphobia, and the trauma of growing up in a dysfunctional home: “At fifty-nine, I am now the age Virginia Woolf was when she took that final, heavy-pocketed walk into The River Ouse. I am the age at which she killed herself, and I am not going to kill myself; but I was by no means always sure of that.” Is this an instance of the author doubling with the characters, who are doubling each other? Probably not, but it does demonstrate why Robin relates closely to the characters, their story, and its author. What could be more personal?

[My] fiction lives or dies on nuance, intimation, observation, insight…, metaphors, moods…

As a fiction writer who studies and practices craft, Robin dissects Mrs. Dalloway’s technical operation, including a pages-long analysis of the function and subsequent interpretation of a single sentence. When explaining her thoughts about Woolf’s purpose for doubling her characters, one of her conclusions is that their dual storylines structure the novel. Clarissa’s character doesn’t experience a psychological shift; she doesn’t learn anything new or change her views or actions. Robin identifies her as the fictional center and her characterization as a portraiture. Septimus, on the other hand, reveals early his thoughts about killing himself, creating tension and suspense as the day develops, concluding the story by taking his life. Structurally, we come to know Clarissa more deeply during her party preparations (the ticking clock adding momentum), while Septimus furnishes drama and a sequence of events that operate as plot.

During this craft analysis, Robin explains the concept of secondary storylines by giving examples from her own fiction. Like Woolf, plot is not her primary interest, so she also adds a structured activity to move the story forward. Robin says her “fiction lives or dies on nuance, intimation, observation, insight…, metaphors, moods…,” which leads her to share an impressive revelation about her own work. She wants to collaborate with her readers, hoping she is adept enough with language and craft know-how to enable the attentive reader to process what she’s doing and grasp her meaning. Robin writes with a sense of hope and trust.

Connection to Septimus and Clarissa

Robin didn’t connect her two decades of being clutched by agoraphobia with Mrs. Dalloway until she looked more deeply while writing this book. Only then did she recognize that her symptoms resembled Septimus’, and as a result, she says, “I understood better what my own experience had been, and I felt grateful for that, and I felt less alone.”

Robin’s negative reaction to Clarissa’s relationship with her daughter leads to a description of Robin’s devoted parenting of three children and readers’ misconception of her female characters as bad mothers. While her children were growing up, Robin’s agoraphobia made it difficult to leave home, so people who didn’t know about her anxieties assumed she was the ideal nurturer, a remark she resented because of its oversimplification and unrealistic implications. Motherhood is a dominant part of Robin’s life and fiction, but recalling the complexity of her experiences as a parent and author helped her recognize Woolf purposely toned back the “juggernaut,” avoiding the risk of it subverting intended themes. As a result, Robin says, “I feel a humble connection to Woolf…”

I have been thinking things through quite a bit, and by things I mean your life.

Robin ends her book with one of our most personal methods of communication: She writes Clarissa Dalloway a letter. “I have been thinking things through quite a bit,” she says, “and by things I mean your life. I have a few pieces of advice.” That advice is extensive and detailed, including what she calls “tough love.” She ends with “I care about you, Clarissa. And in many ways, some of which surprise me, I identify with you.” She signs it, “Your friend, Robin.”

Robin’s book has enough craft analysis to educate any writer, but readers, especially fans of Mrs. Dalloway, will appreciate this rare opportunity to understand how a gifted author is affected and influenced by one of the greats. Robin’s heartfelt, honest account is better than a one-woman theatrical production, better than a documentary. Do you want to know how a classic novel shaped an accomplished writer’s thinking and ultimately her work? Do you want intelligent insights about Virginia Woolf and her book? Go no further. This is it.

~ Nan Cuba

Other Resources of Interest

“The Experience of Reading: An Interview with Robin Black by Curtis Smith”

About Robin Black

Robin Black’s story collection, If I loved you, I would tell you this, was a finalist for the Frank O’Connor International Story Prize, and named a Best Book of 2010 by numerous publications, including the Irish Times. Her novel, Life Drawing, was longlisted for the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, the Impac Dublin Literature Prize, and the Folio Prize. Her fiction has been translated into Italian, French, German, and Dutch. Robin’s most recent book is Crash Course: Essays From Where Writing And Life Collide. Robin’s work can be found in such publications as One Story, The New York Times Book Review, The Chicago Tribune, Southern Review, The Rumpus, O. Magazine, Conde Nast Traveler UK, and numerous anthologies, including The Best Creative Nonfiction Vol. I (Norton) and The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review. Robin lives with her husband in Philadelphia and teaches in the Rutgers-Camden MFA Program.

About Guest Contributor, Nan Cuba

Nan Cuba is the author of Body and Bread, winner of the PEN Southwest Award in Fiction and the Texas Institute of Letters Steven Turner Award; it was listed as one of “Ten Titles to Pick Up Now” in O, Oprah’s Magazine and was a “Summer Books” choice from Huffington Post. Other work has appeared in Antioch Review, Harvard Review, Columbia, Quarterly West, and Chicago Tribune’s Printer’s Row. As a journalist investigating the causes of extraordinary violence, she is featured in a Netflix documentary, The Confession Killer. Cuba is included in Texas Monthly’s “Ten to Watch (and Read)” and is founder and executive director emeritus of Gemini Ink, a nonprofit writing arts center.

Other LitStack Resources

If this article excited your interest like it did ours, you’ll want to click over to Lauren Alwan’s LitStack Rec of Robin Black’s novel Life Drawing, as well Michael Cunningham’s By Nightfall.

Happy reading!

As a Bookshop affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.