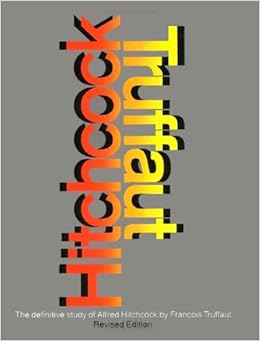

A Definitive study of Alfred Hitchcock, by Francois Truffaut (trans. by Helen Scott).

Before he began directing, Francois Truffaut was a film critic, and before that, a voracious viewer of films. The director’s habit of movie-going reportedly began at the age of eleven, and coincided with his habit of skipping school, until it wasn’t long before film became an obsession—seeing films, reading about films, logging filmographies. Most days, Truffaut saw between three and four films per day—his favorites as many as twenty times. This immersion into the art of film was Truffaut’s education, one he brilliantly parlayed into work as a journalist, writing reviews and covering film festivals for the esteemed publication Cahiers du Cinema, and mainstream magazines such as Elle. It seems inevitable that Truffaut’s fervor for film (as a teenager, he formed a film society called Cercle Cinemane, or the Movie Mania Club) produced the ground-breaking essay, “A Certain Tendency in the French Cinema,” which formed the basis of auteur theory and the French New Wave.

Having gained his confidence on the page, the self-taught Truffaut sought to interview directors whose work he revered, to understand how the films were made, to unlock his heroes’ secrets. With his lifelong friend Robert Lachenay (who would become a film critic and documentary filmmaker), he systematically contacted directors (most of whom agreed to be interviewed), guilelessly offering “free publicity” in return for participation.

One of the first American directors Truffaut encountered was Alfred Hitchcock, through his 1948 film Rope. At the time, Hitchcock wasn’t garnering the rave reviews he would for films like Strangers on a Train or Rear Window, but Truffaut was immediately captivated, recognizing in the English director’s work the qualities he loved most about film: the nod to film noir, the auteur’s view, the references to film inherent in Hitchcock’s technique. For Hitchcock, Rope was an “experiment,” his effort to produce a film that mimicked real time through the use of what appeared to be a single continuous shot; that is, the action in the film never ends at the close of a scene, but continues uninterrupted, an illusion created with a series of disguised cuts.

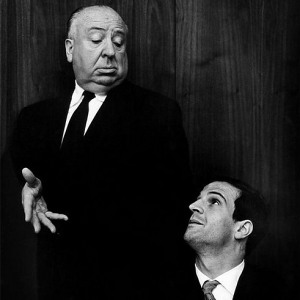

By the mid-sixties, Truffaut had achieved fame with his now-classic film, The 400 Blows, which won the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Director. Soon after, Truffaut approached Hitchcock, who happened to be an admirer, and a series of interviews took place in the fall of 1962 at Hitchcock’s office at Universal Studios. With Truffaut’s longtime colleague Helen Scott serving as translator, the dialogues were recorded, and filled as many as fifty tapes, though the number that survive is said to be twenty-six.

The conversations were published in what is now considered a “bible of film literature” known informally as Hitchcock/Truffaut. What makes this effort so unique are the contrasts between two very different directors—the maverick young artist and the eccentric elder auteur—yet both of whom clearly had an immediate rapport and admiration for each others’ work. In a 1999 review of the book’s reissue, The Boston Globe noted that Truffaut was “well aware his greatness was of a lesser magnitude, and one of his book’s many charms is the deference, unto worshipfulness, author displays toward subject.” This may have been the reason, the review speculates, that the normally reticent Hitchcock was unusually forthcoming with his interviewer, expounding on the hidden tricks and artistic choices in his work—for example, chafing against the usual dark alley murder scene and using instead a crop duster to pursue Cary Grant in an open field at midday.

Truffaut also got to ask Hitchcock about Rope, and the idea behind the editing process:

The stage drama was played out in the actual time of the story; the action is continuous from the moment the curtain goes up until it comes down again. I asked myself whether it was technically possible to film it in the same way. The only way to achieve that, I found, would be to handle the shooting in the same continuous action, with no break in the telling of a story that begins at seven-thirty and ends at nine-fifteen.

More than forty years later, the book is still in print. Truffaut’s longtime colleague, American Helen Scott translated the conversations, while Truffaut chose the book’s layout, its design, and painstakingly selected the accompanying film stills. A portion of the interview is online, twelve hours’ worth of recordings via The Hitchcock Zone, here. A clip of Truffaut’s salute to Hitchcock at his 1979 AFI Life Achievement Award is here.

—Lauren Alwan